Stephen Harding, the eldest son of David Harding and Abigail Brown, was born on February 24, 1808 in Palmyra. He was a cousin to Pomeroy Tucker. Stephen was three years younger than Joseph Smith Jr.

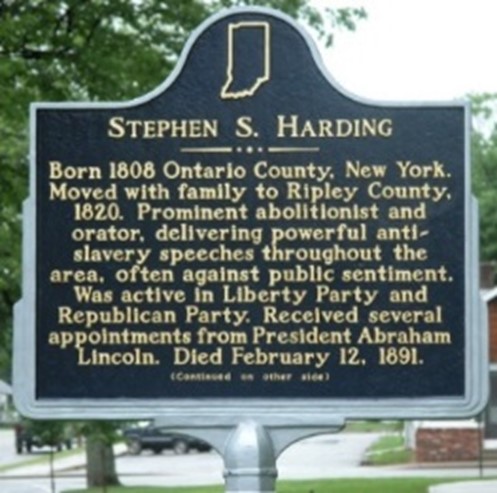

The Harding family moved from Palmyra to Ripley County, Indiana in 1820. Although Stephen only had about nine months of formal school training, he was an avid reader. He studied law in the office of William R. Morris in Brookville, Indiana in 1827 and became a licensed attorney on March 17, 1828 at age twenty. Stephen opened a law office in Richmond, Indiana. Any idle time in his office, he studied Roman and Greek classics and the works of William Shakespeare.

In fall of 1828, Stephen took a steamboat from Louisville, Kentucky to New Orleans, Louisiana. He did this to claim personal property in behalf of a client and to consider establishing a law practice in the South. After a brief sojourn to the South, Stephen grew weary of the slave trade. He dedicated his life to the abolition of slavery. He was called a traitor to his race, a woolly-head, and an apostle of disunion, but he would not recant his view on slavery.

Stephen returned to Indiana in spring of 1829, working his way back home as a clerk on the steamboat Belvedere along the Mississippi River.

A Stolen Manuscript and the Book of Mormon

Shortly after returning to Indiana, Stephen left to spend the summer of 1829 in Palmyra. Stephen was not in Palmyra when the 116 pages were stolen. In a February 1882 letter to Thomas Gregg in response to a request for information about his days in Palmyra, Stephen wrote of his interactions with Pomeroy Tucker, Joseph Smith, Martin Harris, and Oliver Cowdery.[1]

In his letter, Stephen said of the Book of Mormon—

That such a book, replete with self-evident plagiarisms and humbuggery, that sink it below the dignity of criticism, should find tens of thousands of persons of ordinary intelligence throughout Christendom, who have accepted it as a revelation from God to man, is indeed a moral phenomenon unparalleled in the nineteenth century.

Stephen detailed his travels to Palmyra,

In the summer of 1829, I resolved to return to the place of my nativity, in the vicinity of Palmyra, N. Y. . . . I took stage from Cincinnati for Cleveland, from Cleveland down the lake shore for Buffalo, where I saw, for the first time, the great canal, only recently completed. On this I took passage for Palmyra.

In his letter, he told of seeing Joseph Smith in his youth:

I had at the time no certain recollection as to who this “Joe Smith” was; but remembering having seen a long-legged, tow-headed boy of that name, who was generally fishing in the mill-pond at Durfee’s grist-mill on Mud Creek, when my elder brother and I went to the mill. This boy was about three years older than myself.

Stephen wrote of his surprise upon learning of Martin Harris’ involvement with the Book of Mormon—

The fact that such a man as Martin Harris should mortgage his farm for a large sum, to secure the publisher for printing the book, should abandon the cultivation of one of the best farms in the neighborhood, and change all his habits of life from industry to indolence and general shiftlessness, was truly phenomenal.

Stephen then reported that it was “natural that I should seek an early interview with [Martin Harris]. I found him [Martin Harris] at the printing office of the Wayne Sentinel in Palmyra, where the Book of Mormon was being printed. . . . A moment or two after, I was introduced to Oliver Cowdery, Joseph Smith, Sen., and then to the young ‘Prophet’ himself.” Stephen then turned his thoughts to the 116 pages—

I have the authority of Martin Harris himself, who stated that some one hundred and fifty pages, more or less, of the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon had been stolen, lost, or destroyed, by some evil-minded person.

Stephen told of George Crane being approached about the Book of Mormon—

In the neighborhood of Palmyra there lived another prophet, older and wiser than the Mormon prophet. This was old George Crane, who had been born and brought up a Quaker. On one occasion Smith and Cowdery had gone to the house of George, who had manifested some interest in the pretended translation. It was in the evening, and when several chapters had been read, Mr. Crane, who had been an attentive listener, in his straightforward, Quaker soberness said: “Joseph, thy book is blasphemous; and I counsel thee to mend thy ways, or thee will come to some bad end.”

Stephen wrote of interviewing E. B. Grandin and Pomeroy Tucker. He also wrote of dining with Pomeroy.

By this point, Stephen had become “greatly interested, and manifested a desire to hear the miraculous manuscript read.” He went to the Smith log cabin and remained overnight. He recalled—

It was now time to begin the reading of the manuscript, and we retired to the room we had occupied. This was before the days of Lucifer matches, and there being no fire, it took some time before a light could be brought into the room. . . . Cowdery commenced his task of reading at the table, the others sitting around. The reading had proceeded for some time, when the candle began to spit and splutter, sometimes almost going out, and flashing up with a red-blue blaze.

The First Impression of Title Page of the Book of Mormon

About two weeks later, Stephen was present at the Grandin Printing Shop when the first impression of the title page came off the press. He told of the page being “passed to Cowdery, who scanned it carefully, and passed it to the prophet himself, who seemed to be examining every letter, and without speaking gave it into the hands of his father and Harris. It was then returned to Tucker. Of course we all looked at it with more or less curiosity, and the work was pronounced excellent. Tucker, who was my cousin, then handed it to me, saying: “Here, Steve, I’ll give this to you. You may keep it as a curiosity.” I thanked him, and put it carefully in my pocket. (Putting it in a pocket suggests that he folded the title page).

In September 1829, Stephen secured passage on a canal packet for Buffalo. Before he left Palmyra, Stephen recalled, “I had received from Harris and Cowdery the first and second chapters of the Book of Mormon. These, with the title page before mentioned, were carefully put away in my trunk.”

Stephen goes on to tell that “three or four days before my embarkation, Martin Harris, in company with Cowdery, met me at the village, manifesting a great deal of concern at my intended departure.” They followed “me as far as Rochester, and informed me of the commands of the angel, and that I must remain in Palmyra until the printing of the Book of Mormon was completed; after which I must go to the city of London and there remain until the Lord would inform me what to do.”

Stephen tells of coming home from a court session and finding a stranger at his house in 1847: “He was a middle-aged man, an Englishman, named [Robert] Campbell.” He stayed the night at the Harding home. Stephen wrote, “During his stay in my house, I informed him that I had the first title page of the Book of Mormon that was ever printed, and briefly related to him how it came into my possession. I produced it,” Stephen gave the title page to Robert Campbell. Years later, when Stephen arrived in Utah in 1862, “Mr. Campbell was almost the first one to meet me.” Stephen went on to say, “I soon learned that the first title page had been well preserved in the Historical Society and Museum. It had been placed between two panes of window glass in a stout frame. By this means it could be carefully handled and examined without danger of defacement. It has been examined by thousands and thousands; and after my arrival the number increased.”

What have we learned from the Stephen Harding, February 1882 letter?

Stephen possessed the first two chapters of the Book of Mormon, received the first proof sheet of the Book of Mormon or title page, and was invited to share the message of the Restoration in England.

Most important to us are Stephen’s words: “I have the authority of Martin Harris himself, who stated that some 150 pages, more or less, of the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon had been stolen, lost, or destroyed by some evil minded person” and that “Martin Harris and Oliver Cowdery gave him the first and second chapters of the Book of Mormon.” Neither Martin nor Oliver wrote about giving Stephen the chapters.

The Stephen Harding papers are housed in several repositories throughout the United States. Nothing in the cataloging of his papers mentions anything about chapters of the Book of Mormon. The most promising library for us is the Lilly Library at the University of Indiana. In that library are files on Stephen’s reflections on Mormons.

Back in Indiana

By December 1829, Stephen had opened a law practice in Versailles, Indiana. By1830, he was a well-known abolitionist. He gave several anti-slavery speeches at gatherings near his home in southeast Indiana. Stephen took the hardline position that slavery was unconstitutional. In so doing, he became an outspoken leader of the abolition movement in Indiana. It is reported that while giving an abolitionist speech at the Ripley County Courthouse, an angry mob made plans to hang him. Had it not been for the women in town, his life would have been forfeited.

Stephen married Avoline Sprout of Chautauqua County, New York on October 31, 1830 in Ripley County. To their union were born five sons and four daughters.

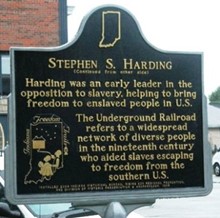

Following their marriage, Stephen was a surveyor and laid out the town of Harding Store. Stephen and Avoline lived in Harding Store near Milan, Indiana. Before long, Harding Store was annexed to Milan. Stephen supported his family by operating a mill and working as a lawyer. His 1840 home in Milan was Station #7 in the Underground Railway system. His red front door designated that it was a stop for runaway slaves. Today, his home is a museum.

Politics

Stephen extolled the tenants of the Whig Party until 1840. In that year, he joined the Liberty Party. In 1842 and 1846, he was nominated as a candidate for lieutenant governor of Indiana by the Liberty Party. He lost both elections, receiving very few votes. When the Liberty Party dissolved in 1848, Stephen joined the Free Soil Party. By 1854, he had aligned himself with the People’s Party, the predecessor of the Republican Party in Indiana. He served on the Indiana Republican Party Central Committee.

In 1862, at the recommendation of influential Indiana politicians, Abraham Lincoln appointed Stephen governor of the Territory of Utah. On March 31, 1862, the US Senate confirmed his appointment without a dissenting vote. His tenure as territorial governor was marred by conflicts with Brigham Young over the practice of polygamy. In his first message to the territorial legislature in December 1862, Stephen defended an anti-polygamy act passed in the US Congress and promised to challenge Mormon dominance in Utah. Using the power of his office, he limited the jurisdiction of the Mormon-controlled probate courts and transferred control of the militia to the office of the territorial governor. Stephen told the US Secretary of State that Mormons were disloyal to the union and Brigham Young was arming his people.

In March 1863, citizens of the Territory of Utah petitioned President Abraham Lincoln to remove Stephen Harding from office. Instead of recalling him, Lincoln appointed Stephen as US consul in Valparaiso, Chile. Due to his wife’s poor health, Stephen declined the appointment on the eve of his departure. In July 1863, President Lincoln appointed Stephen as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Colorado.

As Chief Justice, Stephen was to certify the results of ballots cast in 1865 for admission of Colorado to the Union. Believing the election results altered in favor of statehood, Stephen refused to approve the election. Angered by his refusal, Stephen the Colorado bar charged him with having immoral relations and asked him to resign.

Stephen spends the remainder of his days in Milan, Indiana

In 1865, Stephen left Colorado and returned to Indiana to resume his private law practice in Milan.[2] On June 1, 1867, Stephen Harding wrote from Milan to his cousin Pomeroy Tucker: “I entirely approve your plan of Mormon history.”[3] On November 9, 1867, it was announced, “D. Appleton and Company celebrated publishers of New York are printing Pomeroy Tucker’s book. Mr. Tucker was helped in this undertaking by the Honorable S. S. Harding, Governor of Utah, and Thurlow Weed.”[4]

Stephen retired from practicing law in 1881 due to blindness. Ten years later, he died on February 12, 1891 in his home in Milan at age eighty-three.[5] He was buried in the Greendale Cemetery in Greendale, Indiana.

[1] Gregg, The Prophet of Palmyra, pp. 34–56.

[2] Weekly Indiana State Sentinel, July 26, 1855; “Governor of Utah Territory, 31 Mar 1862,” The Indiana State Sentinel; “Stephen S. Hardin, election of 1848,” The Indianapolis Star, September 11, 1922; “Biography of Stephen Selwyn Harding, 1808–1891”; New York Times, April 8, 1864.

[3] Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 3:82–86.

[4] “History of the Mormons,” Union and Advertiser, November 9, 1867.

[5] “Obituary,” The Morning Democrat [Davenport, IA], February 13, 1891.