Seymour Scovell, one of seven children born to Thomas Scovell Jr. and Rachel Boardman, was born on July 25, 1786 in Orwell, Addison County, Vermont. Orwell was a small rural community that gained a modicum of fame from Mount Independence (Fort Independence) constructed in 1775. The fortress passed between occupation of the British and Colonists during the American Revolutionary War until abandoned at the cessation of hostilities. When Seymour was born, the war was a memory and the village of Orwell was experiencing prosperity. Thus, his childhood was filled with economic advantages of a rural upbringing.

In his youth, Seymour moved seventy miles northeast from his family in Orwell to Hardwick, Massachusetts. The village of Hardwick was known for its textiles and paper mills. Seymour did not come to the village for its commercial enterprises. He came to the village to study medicine. Since there was not a medical school in Hardwick, it is assumed that Seymour studied medicine under a noted doctor in the commercial village.

Resident of Palmyra

Drugstore. Believing himself trained as a medical professional, at age twenty-five Seymour moved to Palmyra and in 1811 set up a medical practice. He became a partner of Gain Robinson in the first drugstore in town. The partnership informed the public that they would sell drugs and medicines, dry wood, paints, and groceries on reasonable terms. They advertised their store (located next to the office and home of Dr. Robinson on Main Street) in the Ontario Repository, perhaps hoping to attract more customers than just Palmyra residents.[1]

Druggists, like Seymour Scovell were more than dispensers of pills. They provided medical advice and prescribed a variety of medications. From the account books of Gain Robinson, it appears he and Dr. Scovell preferred botanic medicine and natural cures to chemical cures, creating concoctions and infusions from herbs. In 1812, he ended his partnership with Gain Robinson. Seeing an advantage for himself, Alexander McIntyre became a co-owner with Gain Robinson in the drugstore.

War of 1812. On June 18, 1812, the US Congress declared war on Great Britain. Within months. John Swift, founder of Palmyra, was appointed Brigadier General of a military unit composed of fifty-seven Palmyra residents—age eighteen to forty-five years—called to colors in the emergency.[2]

Before joining a militia unit, at age twenty-six Seymour married seventeen year old Cynthia Porter, daughter of Noah Porter, on October 18, 1812. Soon thereafter, he received word of his father’s death in Orwell, Vermont. He encouraged his mother and siblings to move from Orwell to Western New York. His extended family did move, but not all settled in Palmyra. With additional family responsibilities, Seymour did not join John Swift and his citizen/soldiers of Palmyra in the early days of the war or in battles at Niagara, Pultneyville, or Sackets Harbor.[3] He waited until 1814 to enlist as a surgeon’s mate in the Nathaniel W. Howell, Esq. Regiment of the New York Militia. When the Treaty of Ghent was signed to end the war in 1815, Seymour returned to his wife in Palmyra.[4]

Enterprising Young Man. Seymour was very successful in business enterprises in Palmyra besides his medical practice. He owned a grist mill and an iron forge. He had a partnership with Philip Grandin, brother of E. B. Grandin, under the name “S. Scovell and Company.”[5] On December 13, 1819, the partnership dissolved by mutual consent. Persons indebted to their firm were requested to make immediate payment without delay. Wheat, rye, pork, etc. were accepted as payment. Seymour continued the business on his own.[6] Joseph Smith “sometimes [found] an odd job to do about the store of Seymour Scovell.”[7]

Seymour was appointed a commissioner of schools in Palmyra. He served from 1818 to 1819.[8] He also served on the board of directors of the Deaf and Dumb School in Palmyra.[9] More important to his rising career, on November 16, 1819 Seymour became the innkeeper at the Eagle Hotel, the largest and finest hotel in Palmyra.[10] Two weeks later on December 1, 1819, Seymour advertised:

Eagle Hotel. Seymour Scovell informs the public, that he has fitted up and furnished the house lately occupied by S. Phelps Esq. in this village for the accommodation of company, and trusts that from his exertions to please, he will receive a share of public patronage.[11]

Erie Canal. Seymour worked on the installation of locks for the Erie Canal. When the Palmyra portion of the Erie Canal was open on November 21, 1821, Seymour built and manned the packet boat Myron Holley, the first boat to launch from Palmyra on the canal. At 11 a.m. on November 21, 1821, a procession began at the Eagle Hotel. It was led by Thomas Rogers II, who acted as grand marshal on that occasion. There was a cannon blast and a band played. Gentlemen requested to give toasts and speeches were seated in the boat. About two hundred watched the proceedings. As the boat began to sail, there were three cheers and more gun fire. After the sailing, about a hundred guests went to the Eagle Hotel and partook of an elegant supper prepared by Major William Rogers.[12]

As other boats came through the canal, each stopped at the Henry Jessup Basin. (A basin was a dug out cove where boats could float in from the main channel of the canal and be loaded or unloaded.)[13] A toll was charged for using a basin. Seymour was the first collector of tolls at the Jessup Basin.

Western Presbyterian Church. Seymour was a trustee, along with Henry Jessup, in the Western Presbyterian Church in Palmyra.[14]

Seymour moved to Lockport

At this point, Seymour looks like a “young man in high standing” in Palmyra. But that appearance of Seymour did not last long. On December 31, 1821, Seymour Scovell was making preparations to sell his home and mercantile businesses—store, hotel, iron forge, and grist mill. A property sale was conducted at his house by Sheriff P. P. Bates and Deputy A. Van Duzer.[15] For those wanting to see his books and store accounts, they were available at the Eagle Hotel. Seymour encouraged all indebted to him to make payment. Unsettled debts were turned over to Frederick Smith, Esq. for collection.[16]

Seymour’s property and businesses didn’t sell right away. It took until 1823 before Seymour and his family were ready to move to Lockport, the county seat of Niagara County, New York. His brothers Asahel and Josiah Scovell joined him in the move. The village of Lockport was so named because it boasted of two planned ports on the Erie Canal. Seymour wanted to be in Lockport before the ports or locks were constructed.

Seymour had a grand hotel built in Lockport which became the most famous hotel in Western New York. He obtained contracts on canal construction and on the building of locks.[17] He and his associates bought 300 acres in the lower town of Lockport from Nathaniel Comstock as an investment. They had the land surveyed and platted. Seymour had real estate near the lock, a sandstone quarry, the Cottage Tavern on the corner of Main and Cottage Streets, and business investments on west Main Street in Lockport.[18] He had packets running before the locks were built. In 1825, Seymour constructed a three-story building on West Main Street. The third story of the house was rented by the local masonic lodge. (The building was torn down in the 1840s when the Erie Canal was widened.) Last, but not least, Seymour was selected as a warden of Christ’s Church, which met at the corner of Market and Vine Streets. Today the building is called “The House of God Church.”[19]

The Year 1828

On June 14, 1828, Martin Harris carried the 116 pages to Palmyra. He had the manuscript in his possession for three weeks or until about July 7, 1828. During those weeks, Martin showed the manuscript to any “prudent” person who called. Would forty-six year old Seymour Scovell be considered a prudent person in 1828? Yes, but he was living 90 miles away from Palmyra in Lockport, New York. He had moved away from Palmyra five years before.

Why is Seymour Scovell on our list of suspects?

The only account of the 116 page manuscript being passed to “a certain Dr. Seymour” is found in the William Hine interview published in Arthur Deming’s, Naked Truths about Mormonism (Oakland, CA: Deming & Company, 1888).

Before examining the interview, let us learn about the lives of Arthur Deming and William Hine.

Arthur Buel Deming. Arthur was born in 1838 in Cincinnati, Ohio. His father, Miner Deming, was a sheriff in Hancock County, Illinois when the Latter-day Saints were living in Nauvoo. Arthur’s father died a year after Joseph Smith in 1845. Arthur grew up blaming “the Mormons” for his father’s early death.

Arthur became a traveling salesman, representing companies in California and New York City. In 1884, he sold goods for W. L. Hurlbut & Company in San Francisco. In 1898, he moved from Oakland, California to New York City. In the city, Arthur Deming said he had a vision from heaven telling him to warn J. P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie of impending doom. He also professed that “Mormon Leaders in Salt Lake City had been sending out secret agents to steal his writings and collected statements on the history of Mormonism.” His shouting of these claims led to his being taken to police headquarters and committed to a psychiatric ward at Belleview.

William Riley Hine (1803-1889). William and three of his daughters were members of the Colesville New York Branch in 1830. They were supportive of branch leaders Joseph Knight and Hyrum Smith. They moved to Ohio with the early Saints. William stated, “After I came to Kirtland, in conversation with Martin Harris, he has many times admitted to me that this statement about his wife and the one hundred and sixteen pages, as above stated, is true.”

Now what of the above statement? William Hine was interviewed by Arthur Deming in 1885. In the interview eighty-two year old Hine claimed—

They [Joseph Smith, Martin Harris, and Oliver Cowdery] soon missed the one hundred and sixteen pages and followed [Lucy Harris] into the road and demanded them of her. She refused, and said if it was the Lord’s work you can translate them again, and I will follow you to the ends of the earth. Dr. Seymour came along and she gave them to him to read, and told him not to let them go. Dr. Seymour lived one and a half miles from me. He read most of it to me when my daughter Irene was born. He read them to his patients about the country. It was a description of the mounds about the country and similar to the ‘Book of Mormon.’”

The first question—Is the Hine/Deming reference to Dr. Seymour Scovell of Palmyra/Lockport or to Dr. Ezra Seymour of Colesville? Historian Dan Vogel wrote that the Dr. Seymour was Ezra Seymour of Colesville.[20] That’s impossible. There is no record of Lucy Harris ever being in Colesville or of Ezra Seymour coming to Palmyra. Colesville is 150 miles from Palmyra.

Ezra Seymour of Colesville was sixty-six years old when the 116 pages were stolen in 1828. In 1803, Ezra became a medical doctor. Three years later in 1806, he was elected vice-president of the Medical Society of Broome County, New York.[21] In 1811, Ezra moved to Colesville, New York, the same year Seymour Scovell moved to Palmyra. Ezra was the first physician in Colesville. It was said of him, “His professional knowledge and skill was at least respectable.”[22] He became intemperate and ended his practice before the 116 pages were stolen.

If the interview is to be believed, William Hine thought Dr. Ezra Seymour had the pages but the timing of a Seymour possession is off. Hines writes of his having the pages at the time his daughter Irene Hine was born. The problem is Irene Hine was born in 1825 and the pages were stolen in 1828. At this point, I do not believe that Lucy Harris passed the pages to Dr. Seymour Scovell or Dr. Ezra Seymour.

Seymour moves to Lewiston, New York

In 1829, much of the land acquired by Seymour in Lockport was sold to the Albany Land Company. On November 2, 1829, Seymour and his family and Polly Cobb Parker, sister of Lucy Harris, and her husband William Parker, moved to Lewiston, New York, a distance of 20 miles from Lockport. (Lewiston was the first town in Niagara County, and Lockport was the second.) The reason for Seymour’s move was an appointment by President Andrew Jackson to be the collector of customs for the district of Niagara and inspector of revenue for the port of Lewiston, positions held for nearly thirty years.[23] The posts proved very profitable since the collector of customs received seventy percent of imports in addition to his salary.[24] For example, in 1831 he received $1,359.[25] Seymour was active in promoting the erection of a suspension bridge in Lewiston.[26] He served on the board of directors of the Lewiston Suspension Bridge Company.[27]

Seymour Home in Lewiston

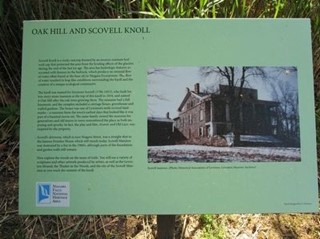

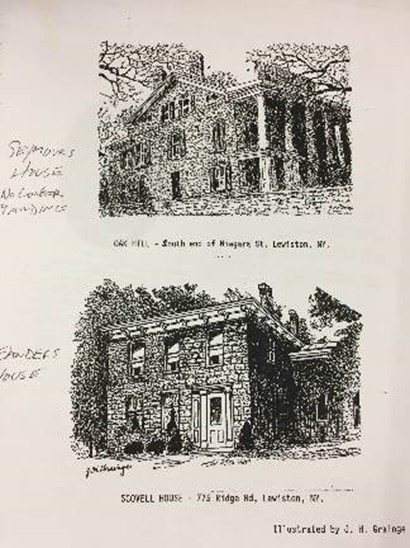

In 1834, the Seymour Scovell home was built by John Cleghorn on top of Scovell Knoll, a rocky outcrop. The elegant home was known as the Oak Hill Mansion because of a grove of oak trees growing nearby.[28] Legend has it that Seymour hid fugitive slaves in the subterranean cellars of the home. The legend is based on a tunnel located in the basement. The house had a servants’ annex, a large stone stable, a terraced garden, and a greenhouse. The driveway from his house leading to another famous dwelling—the Frontier House—is today Niagara Street.

Playwright Joseph O. Kesselring modeled the set for his play Arsenic and Old Lace after the Oak Hill Mansion. The home was acquired in 1963 by the New York State Power Authority and turned over to the New York State Parks Commission. The property was vandalized and destroyed by fire in 1964.[29] The carriage house was destroyed in 1971. The property is now part of Art Park’s 4th Street entrance in Lewiston.[30]

Always an Enterprising Man

When the Lewiston Railroad was incorporated on May 6, 1836, Seymour was asked to serve on the board of directors.

On January 17, 1839, Seymour married Emaline Alice Ways, daughter of Benjamin Ways and Mary Ann Evans, exactly one year after the death of his first wife. Seymour and Emaline became the parents of three children.

On April 21, 1847, Seymour was elected supervisor of Lewiston, which is equivalent to being elected mayor.[31] On January 21, 1848, Seymour became a member of the Niagara LaSalle Masonic Lodge No. 132 and the Lewiston Frontier Masonic Lodge.[32]

Death of Seymour Scovell

On February 12, 1852, Seymour died of apoplexy in Lewiston at age sixty-six.[33] He was buried in Row G in the First Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Lewiston. In the Lewiston—Past, Present and Future, Seymour was described as “a genial, hospitable man and the old house has been the scene of many brilliant parties and weddings.”[34] According to the New York Wills and Probate Records, Seymour’s estate was probated on November 23, 1854 in Niagara, New York.[35]

On February 15, 1870, Seymour’s widow, Cynthia Porter Scovell, died at age seventy-five. Following her death, her descendants donated an alms basin, an altar cross, and a glass window to the St. Paul’s Episcopal Church at the corner of Niagara and Plain Streets in Lewiston.[36]

Children of Seymour and Cynthia Scovell

1. Thomas Porter Scovell (1814–1896). He was born in Palmyra. Thomas came to Lewiston in 1837. He graduated from Yale College in the class of 1836 and delivered the valedictory address on that occasion. He started a newspaper in Lockport known as the Frontier Sentinel. From 1839 to 1846, he published the Niagara Democrat. He also served as an insurance agent and the town clerk of Lockport for forty years. He resigned in 1892 on account of feeble health. He died of paralysis at the Oak Hill Mansion at age eighty-two.[37]

2. Leander Kutusoff Scovell (March 5, 1817–1887). He was born in Palmyra. He was named after the Russian Field Marshall, Prince Mikhail Kutusoff, who defeated Napoleon during the invasion of Russia in 1812. Leander served as town supervisor and assessor of Lewiston. He was president of the Lewiston and Queenstown Suspension Bridge Company. In 1846, he was initiated into the Sacarissa Lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows in Lewiston. He served as senior warden and vestryman of the St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. The left stained glass window in the St. Paul’s Church is a memorial to Leander.[38] He married Emeline Alice Ways on January 17, 1839. To their union was born three children.

3. Cynthia R. Scovell (August 13, 1818–1904). She was born in Palmyra. On September 13, 1838, Cynthia was married to Philip Brotherson at Lewiston by Reverend Mr. Murray. Philip Brotherson was the cashier of the Suspension Bridge. In 1852, Cynthia married William Wilson Anstey of New York City.[39]

4. Maria P. Scovell (1824–1893). She was born in Palmyra. Maria married Henry F. Hotchkiss. She had no children. She was a member of the St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Lewiston. She was buried in the Lewiston Village Cemetery. The large cross in the center of the altar of the St. Paul’s Church was dedicated to her memory on Christmas Day 1898.[40]

Children of Seymour and Emaline Scovell

1. Joseph Evans Scovell (died as an infant).

2. Mary Emaline Scovell.

3. Leander W. Scovell.

[1] “New Druggist Store,” Ontario Repository, February 26, 1811.

[2] Clark, Military History of Wayne County, New York, pp. 245–246.

[3] Cook, Palmyra and Vicinity, p. 15.

[4] Margaret S. Lewiston, Crown Jewel of the Niagara [2001], pp. 61, 62–63, 72; Seymour Scovell – Grandeur of Oak Hill; Citation for War of 1812 Service Records.

[5] “Mortgage Sales,” Palmyra Register, February 10, 1819.

[6] “Dissolution,” Palmyra Register, December 14, 1819.

[7] “Origin of the Mormon Imposture, ” Newspaper clipping, June 24, 1851; Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 3:49; Turner, History of the Pioneer Settlement of Phelps and Gorham’s Purchase and Morris’s Reserve.

[8] Town of Palmyra Minutes.

[9] “Deaf and Dumb School at Palmyra New York,” Geneva Gazette, April 17, 1822.

[10] P. Bates, sheriff and A. R. Swift, deputy, “By virtue of a Writ . . .,” Newspaper clipping. In author’s possession.

[11] “Eagle Hotel” advertisement, Newspaper clipping. In author’s possession.

[12] “The Launch,” Western Farmer, November 21, 1821.

[13] “Death of Henry Jessup, Newspaper clipping, November 1887. In author’s possession.

[14] “Bicentennial Celebration 1817–2017: “Gleanings from the First 200 Years,” Western Presbyterian Church, Palmyra, NY; The Woman’s Society of the Western Presbyterian Church, Palmyra: Wayne County, New York (Rochester, NY: The Herald Press, 1907).

[15] “By Virtue of a…,” Palmyra Register, June 7, 1820.

[16] “Notice,” Palmyra Western, December 31, 1821.

[17] Muriel Scovell Ogden, The Scovells of Lewiston, Lockport and Cambria.

[18] “Lewiston’s Scovell House erected 127 Years Ago,” Lockport NY Union, April 6, 1966.

[19] “Seymour Scovell and the Erie Canal; those were the Days, my Friend.” In author’s possession.

[20] Mackay and Dirkmatt, From Darkness unto Light, p. 95; Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 2:481; “W. R. Hine’s Statement,” Naked Truths about Mormonism.

[21] Broome County Internet Archive.

[22] Deming, Naked Truths about Mormonism.

[23] “Seymour Scovell of Lockport . . .,” Geneva Gazette and Mercantile Advertiser, November 4, 1829.

[24] Dr. Seymour Scovell, Correspondence from the Historical Association of Lewiston, Inc.

[25] Niagara Courier, July 20, 1842.

[26] Dr. Seymour Scovell, Historical Association of Lewiston, Inc.

[27] Muriel Scovell Ogden, The Scovells of Lewiston, Lockport and Cambria.

[28] “Oak Hill and Scovell Knoll,” Niagara Falls National Heritage Area, Tourist Sign; Linus Ormsby, “Historic Lewiston Landmark Falls Victim to Area Progress,” Niagara Falls Gazette, February 5, 1967.

[29] Michelle Kratts, “Portrait of an Odd Fellow,” in Lewiston Public Library.

[30] Ogden, The Scovells of Lewiston, Lockport and Cambria.

[31] “Seymour Scovell and the Erie Canal.”

[32] Lewiston, Crown Jewel of the Niagara [2001], pp. 61–63, 72; Seymour Scovell – Grandeur of Oak Hill.

[33] Lewiston Democrat Courier, February 14, 1852.

[34] “Dr. Seymour Scovell.” In author’s possession.

[35] New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659–1999.

[36] “Seymour Scovell and the Erie Canal.”

[37] Lockport Democrat Journal, August 7, 1896.

[38] Muriel Scovell Ogden, The Scovells of Lewiston, Lockport and Cambria.

[39] Niagara Dem. and Bal., September 19, 1838.

[40] Muriel Scovell Ogden, The Scovells of Lewiston, Lockport and Cambria.