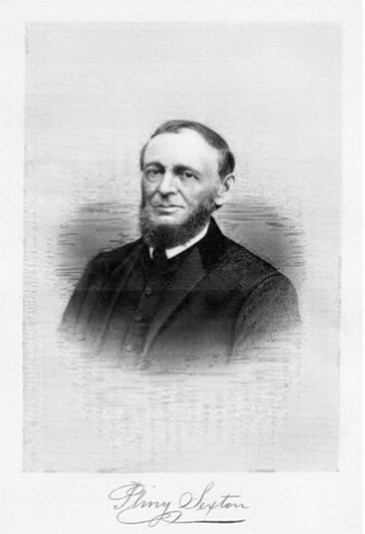

Seymour connection to Pliny Sexton

Pliny Sexton, son of Pliny Sexton and Salome Kent, was born on January 31, 1796 in Springfield, Massachusetts. At age three, his parents took him from Massachusetts to Western New York. The Sexton family settled temporarily near the present village of Marion, about seven miles from Palmyra. Within a year, they had moved to the village of Palmyra and were living on Mill Street when his father died in 1800.[1]

In December 1801 at age five, Pliny journeyed with his mother to visit her mother (his grandmother) in Suffield, Connecticut, a distance of 290 miles. Pliny and his mother remained in Connecticut until 1803, when they again journeyed westward. Pliny wrote, “I think we stayed on the Hayden farm until after 1806 as I recollect working there at the time of the Great Eclipse in 1806.”[2] After he and his mother returned to Palmyra, his mother married Eli Seymour.

At this point, we move from a recitation of facts to the William Hine interview published in Arthur Deming’s, Naked Truths about Mormonism (Oakland, CA: Deming & Company, 1888). In the interview, Hine claimed the 116 page manuscript was passed to “a certain Dr. Seymour”:

W. R. Hine: “Martin’s wife cooked for them [Joseph Smith, Martin Harris, and Oliver Cowdery], and one day while they were at dinner she put one hundred and sixteen pages, the first part they had translated, in her dress bosom and went out. They soon missed the one hundred and sixteen pages and followed her into the road and demanded them of her. She refused, and said if it was the Lord’s work you can translate them again, and I will follow you to the ends of the earth. Dr. Seymour came along and she gave them to him to read, and told him not to let them go. Dr. Seymour lived one and a half miles from me [in Colesville]. He read most of it [116 pages] to me when my daughter Irene was born; he read them to his patients about the country. It was a description of the mounds about the country and similar to the “Book of Mormon.” I doubt if the one hundred and sixteen pages were included in the “Book of Mormon.” After I came to Kirtland, in conversation with Martin Harris, he has many times admitted to me that this statement about his wife and the one hundred and sixteen pages, as above stated, is true.[3]

Historian Dan Vogel contends that the Dr. Seymour in the Hine/Deming reference was Ezra Seymour of Colesville.[4] What Dan Vogel did not know was the mother of Pliny Sexton married Eli Seymour in Palmyra and there is a direct connection between Eli Seymour and Ezra Seymour.

His Youth

At age nine, Pliny worked for Sylvanus Conant in a brickyard on the creek flats about two miles west of Palmyra.[5] At age eleven, he and his family moved to Walworth, New York, where Pliny drove cows from Walworth to Lake Ontario, a distance of 45 miles. At age thirteen (1809), he and his family moved to Johnstown, a distance of 170 miles from Palmyra. In Johnstown, Pliny was an apprentice for seven years to Caleb Johnson, a silversmith and watchmaker.

In the fall of 1818 at age twenty-one, Pliny returned to Western New York and worked in Auburn, a distance of 45 miles from Palmyra. In Auburn, he honed his skills as a journeyman making mathematical instruments such as surveyors’ compasses.

A Silversmith in Palmyra

In 1819, Pliny returned to Palmyra and opened a shop on Main Street. The shop was built by his “brethren of the Society of Friends—Quakers.” The significance of Pliny having a shop on Main Street is the fact that Quakers kept to themselves and did not have a storefront in the heart of Palmyra. His shop puts Pliny in a different category than the “brethren of the Society of Friends” like Lemuel Durfee and Martin Harris.

Pliny’s shop was located on the present site of the Episcopal Church. Pliny was the first silversmith in the village of Palmyra. In his shop, Pliny made and sold sleigh bells, silver spoons, and compasses. If wanting something from his shop, in the Palmyra clerk’s office is a surveyor compass made by Pliny Sexton. This is the seal that appears on his silver work.

Marriage in 1822

Pliny married four times. Each marriage was to a Quaker and each took place in Palmyra.

His first wife Margaret Turner (1797-1831) was the sister of Orsamus Turner, a publisher and one of our suspects. The marriage of Pliny and Margaret took place at the Lemuel Durfee Sr. meetinghouse. At the June 27, 1823 Quaker meeting, “Mr. and Mrs. Sexton being present acknowledged the charges against them were true and manifested repentance and sorrow for their guilt and prayed forgiveness of God . . . and agreed to make a public confession next Sabbath.”[6] The charges against them were not enumerated.

Pliny and his bride lived at the corner of Main and Washington Street. To support his wife and four children from this marriage, Pliny worked as a silversmith. He made a comfortable, but not lavish income until 1823 when he sold the first cooking stoves and sewing machines in Palmyra. It was the selling of cooking stoves that brought him wealth. By 1825, Pliny had the means to join men of high standing erect the Jenner Block in Palmyra. The block was named for James Jenner, the ancestor of Bruce/Caitlyn Jenner of Olympic fame.

Circumstances in Pliny Sexton’s life when the 116 Pages were Stolen

1. Pliny was thirty-two years old when the 116 pages were stolen.

2. He attended the Quaker meetings on the Lemuel Durfee farm and was referred to as “elder.”

3. He was the proprietor of a hardware store on the Jenner Block.

4. He had a small animal business like other Quakers in Palmyra. His name appeared often in the “Lemuel Durfee Account Farm Book, August 3, 1825 to July 10, 1829.”

5. He and his family lived in this house (built in 1827) on East Main Street in Palmyra.

6. On February 24, 1828, Pliny was elected a fire warden in Palmyra. Three months later, he helped organize Palmyra’s first fire company.

7. Although his educational opportunities had been hit and miss, by this period Pliny enjoyed reading and was surprisingly familiar with great writers. He especially liked quoting English poetry.

Pliny became a Man of High Standing in Palmyra

By the time his first wife Margaret Turner Sexton died on May 27, 1831 at age 33 years, 9 months, and 25 days, Pliny had joined Thomas Rogers II, George Beckwith, and Philip Grandin as a stockholder and director of the Wayne County Bank of Palmyra. He had also become a close friend of E. B. Grandin, who wrote of attending the “funeral of Mrs. P. Sexton who died Friday morning last. [The funeral was held in the] friend’s meetinghouse near Lemuel Durfee’s home—a lady preached a short sermon.”[7]

Pliny was married to Susan Aldrich on November 1, 1832 at the meetinghouse on the Lemuel Durfee farm. Susan died within three years of their marriage on August 18, 1835. No children were born to their union.

In 1833, Pliny signed the “Testimony of 51 Neighbors” later printed in Mormonism Unvailed.[8]It contains the first written account of Pliny knowing anything about Joseph Smith.

On September 22, 1836, Pliny married a third time to widow Hannah Titus Van Alstine, a Quaker minister. Mary Durfee, daughter of Lemuel Durfee Sr., was very close to Pliny and his wife Hannah. Mary wrote in her diary:

January 27, 1837: “Went to Pliny S. Hannah is sick with an affection of the lungs.” June 25, 1837: “Pliny Sexton & Hannah . . . dined with us they went away from 4 to 5.” January 4, 1838: “Hannah Sexton addressed the people [at a Quaker meeting in Farmington] in a clear feeling & energetic manner.” January 3, 1839: “Attended Meeting. It was large. Thomas McClintock delivered an important testimony. Hannah Sexton likewise; evidence was sufficient to my mind, that neither of the communications were ‘cunningly devised fables.’” June 22, 1839: “Pliny Sexton & wife called here. Hannah is quite unwell staid till after dinner.” January 21, 1840: “We went to P. Sextons on a visit. H. is ill with a nervous complaint.” February 17, 1840: “Hannah Sexton confined to her bed.” August 11, 1840: “Attended Abigail Harris’s funeral [the sister-in-law of Lucy Harris] it rains Gideon Herrendeen & wife dined with us Pliny Sexton & wife.”[9]

By 1837, Pliny had stopped his day-to-day labor in the hardware store. He sold his hardware store to Stephen Seymour, a half-brother.

In 1840, when the Wayne County Bank of Palmyra failed, Pliny did not return to the hardware business.[10] He retained his interest in banking and formed a partnership with George Cuyler (a man in high standing in Palmyra) in the Cuyler Bank. The bank was opened in the defunct offices of the Wayne County Bank. Serving as president of the bank was George Cuyler, an attorney who had owned and operated a competing hardware store in Palmyra and had been a partner with Pomeroy Tucker in the Wayne Sentinel.[11]

Pliny was the vice president of the Cuyler Bank. Stephen Seymour, who failed in the hardware business, served as cashier. Also working at Cuyler’s Bank was David S. Aldrich, a Quaker and relative of Pliny’s second wife Sarah Aldrich. David liked to boast that he was the clerk who sold Joseph Smith his first black suit and that Martin Harris picked up the bill. For any collectors among us, an 1854 $5 Cuyler Bank note is currently being sold online.[12]

When Pliny was sure of a steady income from the bank, he purchased the George Beckwith Mansion. The mansion has 4,244 square feet of living space on two main floors. There are eight fireplaces in the home, a butler’s staircase, and a servants’ quarters. Pliny was the second owner of the mansion.

In addition to the Beckwith Mansion, Pliny purchased an old mill pond which he converted into a habitable region and sold lots.[13]

On September 10, 1849, Pliny’s third wife, Hannah Titus Van Alstine Sexton, died at age 46 years, 6 months, and 5 days.

Anti-Slavery and Women’s Rights

Pliny was heavily committed to the anti-slavery movement in Western New York. He believed slavery was not just a curse, it was a crime. Beginning on October 3, 1835, his name appeared in an open letter to the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. The letter called for freeing all slaves. In March 1840, Pliny accepted the post as assistant chairman of the Farmington/Waterloo Western Anti-Slavery Convention. He helped organize the New York State Anti-Slavery Society. In 1842, he was a counselor in the society, and in 1847 on the executive committee. In May 1852, Pliny made a financial donation to the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Pliny turned his first home in Palmyra into a station on the Underground Railroad. In this way, he helped many slaves escape to Canada.[14] No social ostracism or fear of penalties deterred him from giving shelter to runaway slaves.

In addition to helping slaves on their road to freedom, Pliny heralded the cause of women. Beginning in 1850, he served as a delegate to the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. He recorded, “The Convention meets in Brinley Hall, a commodious room in a central part of the city. At 9 1/2 o’clock, the hall is filling up rapidly. Many distinguished persons have already arrived. Among them I notice Lucretia Mott and Rebecca Plumley of Philadelphia.”[15]

His Wealth Increases

In 1853, Pliny married a fourth time to Charlotte Snow, twenty-four years his junior.

According to the US Federal Census of 1860, at age sixty-four Pliny had a real wealth of $20,000 and a personal wealth of $10,000. He must have had a type of pre-nuptial agreement with his wife Charlotte, for she had a real wealth of $400.

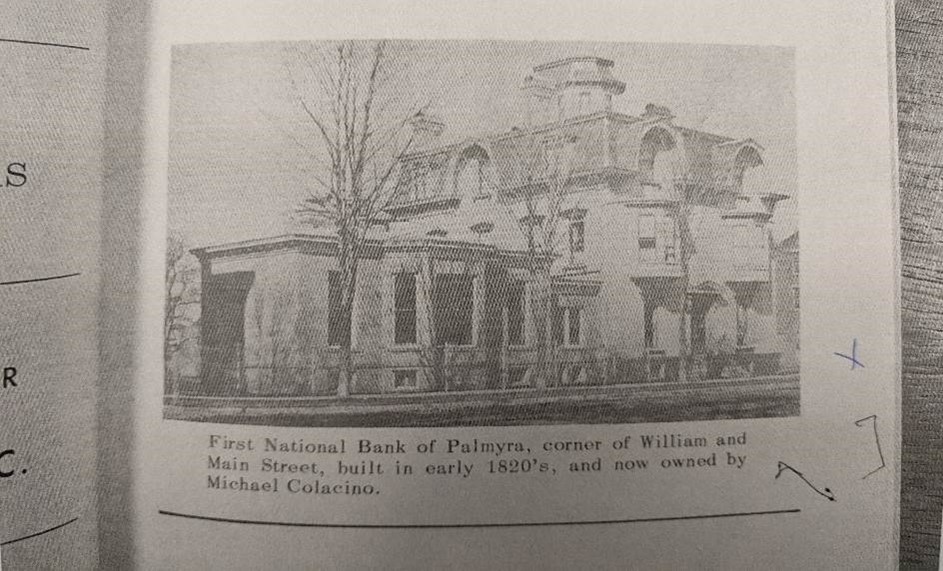

In 1864, Pliny Sexton and George Cuyler organized the First National Bank of Palmyra. At that time, George served as president of the bank, and Pliny as vice-president.[16] Stephen Seymour was second vice president and cashier. When Stephen served in the Thirty-ninth Infantry during the Civil War, Pliny took over as cashier of the bank. [17]

Pliny was involved in other enterprises besides the bank. He was director of the Palmyra Gas Company, treasurer/director of the Star Paper Company, and director of the Canandaigua Railroad Company.[18] He owned lumber property near the Straits of Mackinac and Lake Huron in Michigan. The lumber was transported via the Great Lakes and the Erie Canal to basins in Palmyra.[19]

The 1870 US Federal Census reveals that seventy-four year old Pliny Sexton had a real wealth of $35,000 and a personal wealth of $50,000. The editor of the Newark Courier wrote on July 8, 1875, “George Cuyler and Pliny Sexton are worth to Palmyra a whole barnyard full of men.”[20] Less than a year later, George Cuyler died. Upon his death, Pliny became president of the bank.

Death of Pliny Sexton

In 1881, Pliny Sexton was one of the oldest and most highly respected citizens of Palmyra. One historian claimed, “In general terms it is wholly proper to state that no one has exerted a wider influence for good in this community.” On March 26, 1881, Pliny died at his residence at age 85 years, 1 month, and 26 days.[21] His remains were carried to the Palmyra City Cemetery by his grandchildren.

On May 14, 1883, Pliny’s widow and fourth wife, Charlotte Sexton, died at age 63 years, 6 months, 26 days.

[1] Pliny Sexton File, in Palmyra Community Library.

[2] Pliny Sexton Autobiography.

[3] Deming, Naked Truths About Mormonism.

[4] Mackay and Dirkmatt, From Darkness unto Light, p, 95; Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 2:481; “W. R. Hine’s Statement,” Naked Truths about Mormonism.

[5] Pliny Sexton File in Palmyra Community Library.

[6] Records of the Church of East Palmyra. In author’s possession.

[7] Egbert B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[8] Howe, Mormonism Unvailed, pp. 366–367.

[9] Mary Durfee Diary, 1837–1838.

[10] “Sexton,” in Durfee Scrapbook No. 3, 1876–1883.

[11] “Death of George W. Cuyler,” Durfee Scrapbook, no. 3, 1876–1883.

[12] “A Case of Usury-Important to Brokers and Borrowers,” Buffalo Weekly Republic, January 16, 1849.

[13] “A Case of Usury-Important to Brokers and Borrowers,” Buffalo Weekly Republic, January 16, 1849.

[14] “Pliny Sexton,” Democrat and Chronicle [Rochester, NY], March 28, 1881; “Sexton,” in Durfee Scrapbook No. 3, 1876–1883.

[15] New York Daily Tribune, October 24, 1850; Pliny Sexton Autobiography; “The Proceedings of the Woman’s Rights Convention, Held at Worcester, October, 23d & 24th, 1850: (Boston: Prentiss & Sawyer, 1851), 3–4; National Anti-Slavery Standard, April 15, 1852, and May 20, 1852.

[16] Pliny Sexton File, in Palmyra Community Library; “Sexton,” in Durfee Scrapbook No. 3, 1876–1883.

[17] Military History of Wayne, Co. N.Y.; Directory of the Town of Palmyra.

[18] Directory of the Town of Palmyra.

[19] “Palmyra Affairs,” Newark Courier, March 21, 1872.

[20] “Local and Miscellaneous,” Newark Courier, July 8, 1875.

[21] “Died—Pliny Sexton, Aged 85,” Durfee Scrapbook No. 3 1876–1883.