Luther Bradish was the seventh of eight children born to Colonel John Bradish Jr. (a veteran of the American Revolutionary War) and Hannah B. Warner. Luther was born on April 15, 1783 in Cummington, Hampshire County, Massachusetts. In that small rural community, named for the original land owner, Colonel John Cumming, Luther grew to manhood. He attended Williams College—the second oldest college in the state—in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Two letters addressed to his parents while a college student are extant—January 7, 1803, and June 28, 1803. The letters contain insights about maturing to manhood, details about his experiences at college, and comments and questions about his family’s well-being. In 1804, at age twenty-one Luther graduated from Williams College.

After working briefly as a teacher, Luther entered the legal profession. He interrupted his law practice to volunteer in the War of 1812. After the war, Luther returned to Cummington and married his childhood sweetheart, Helen Elizabeth Gibbs, on April 21, 1814. Unfortunately, Helen died from childbirth complications in 1816, as did her stillborn son. Within a year, Luther married Lucy Abigail Durkee in St. Lawrence, New York.

In 1819, US Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned Luther Bradish to pursue a treaty between the United States and the Ottoman Empire regarding commerce and shipping on the Mediterranean Sea. In 1819, the Empire controlled much of Southeastern Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. Luther succeeded Philadelphian David Offley, who interceded on behalf of American shippers with the Empire’s regencies along the Barbary Coast. Offley’s effectiveness was limited due to the United States lacking official relations with the Ottoman Empire.

Luther served as a special envoy of John Quincy Adams from 1819 to 1825. He, like his predecessor, did not succeed in securing a treaty with the Ottoman Empire. A treaty was not signed until May 1830, when Andrew Jackson was US President and a different US negotiating team prevailed with the Ottoman Empire.

For six years (1819-1825), Luther traveled extensively in Europe and the Middle East. He learned Arabic and German and was conversant in several native African languages. He traveled to Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, “where he spent considerable time in the great capitols and studied assiduously their languages, manners and antiquities.” He visited several key archaeological sites and was aware of temple raiders near the Nile who were excavating and removing Egyptian treasures and artifacts. He also trafficked in Egyptian artifacts, sending some to New York and others to Philadelphia.

Isaac Carey and Isaac Lea—Publishers in Philadelphia

After returning to the United States, Luther played a mediating legal role between author James Fenimore Cooper and publishers Isaac Carey and Isaac Lea of Philadelphia, one of the best publishing houses in America. Cooper, a famed American novelist who wrote of frontier and Indian life (his greatest work being The Last of the Mohicans), was writing a new novel in France.[1] Luther negotiated contracts for Cooper with Carey and Lea, assuring both author and publisher of a fair transaction.[2] In 1827, Carey and Lea wrote to Luther Bradish:

[How] dangerous [it is] to trust a new book in the hands of any one unless it is almost perfect. There is so much desire to show an acquaintance with what is generally known, that it is hardly possible for anyone to keep to himself . . . and if there be faults, they are almost certain to be made known.

Carey and Lea also wrote, “We know perfectly well you would not put it into the hands of anyone” else. Luther negotiated a contract of $4,500 for James Fenimore Cooper with publishers Lea and Carey for The Red Rover (1827).[3]

Luther Runs for Political Office

Before settling down, Luther traveled extensively in Western New York. On January 24, 1827, his name was mentioned in the Geneva Palladium as having letters at the post office in Geneva, twenty-five miles from Palmyra.

Luther finally settled in Moira (named for the Earl of Moira) in the fourth district on the western border of Franklin County, New York. With money earned as a special envoy for the US Secretary of State and from legal work, Luther purchased large tracts of land in Moira and was considered a wealthy and prominent citizen of the community.

In 1827, Luther Bradish was elected to represent Franklin County in the New York State Legislature, serving from 1828 to 1830.[4] When the legislature was in session, Luther lived in Albany.[5] He is credited with the motion to print the annual Red Book of theHouse of Assembly. Luther was named in the book for pushing forward the agenda of canals and other internal improvements in the state of New York.[6]

Luther Bradish ties to Palmyra

Located in the Luther Bradish Papers are several letters connecting him to Palmyra, prior to 1828.[7] First and foremost are his family ties to Palmyra. His father, mother, and siblings settled in Palmyra as early as 1810. There, they became prominent members of the Episcopalian Church. His father died in Palmyra on June 1, 1825. His mother died three years later on December 5, 1828. His sister Chloe Bradish married Gain Robinson. His nephew, son of Chloe Bradish, wrote to Luther, “You have some dear friends [here] who would give you a cordial welcome if you were to sell your land holdings in Franklin County and move to Palmyra.”[8] Luther never did so. His brother Charles Bradish resided in Macedon near George Crane. Another brother, Calvin Bradish, moved to Lenawee County, Michigan, as did George Crane.

John H. Gilbert, the typesetter and compositor of the Book of Mormon, stopped in Albany on his way to New York City to call on Luther Bradish. On April 18, 1829, Philip Grandin, brother of E. B. Grandin, wrote a letter to Luther Bradish.[9]

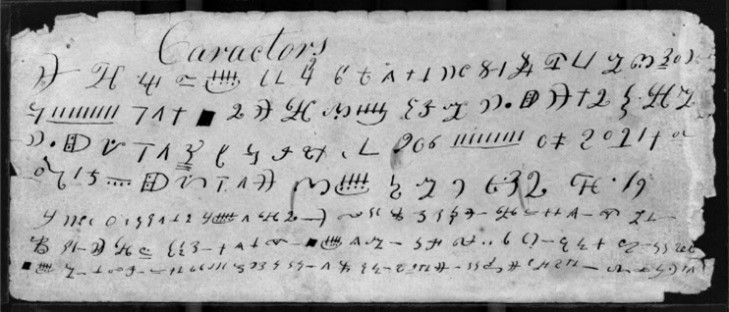

“Egyptian Caractors” copied from the Gold Plates

In Harmony, the Prophet Joseph Smith “commence[d] copying the caractors off the plates” in anticipation of the arrival of Martin Harris.[10]

Lucy Mack Smith wrote—

It was agreed that Martin Harris should follow [Joseph to Harmony Pennsylvania] as soon as Joseph should have sufficient time to transcribe the Egyptian alphabet which Mr. Harris was to take to the east and through the country in every direction to all who were professed linguists to give them an opportunity of showing their talents in giving a translation of the characters.[11]

Martin went to Harmony, picked up the characters, and then went east “in every direction to all who professed to be linguists.” (Notice that Martin was not told which linguists to see. It appears he made that decision himself.)

Martin returned to Palmyra from Harmony, and showed the characters to Reverend John Clark of the Episcopalian Church. Clark wrote—

Martin Harris called at my house in Palmyra, one morning about sunrise. . . . Previous to this, I had but very slight acquaintance with Mr. Harris. He had occasionally attended divine service in our church. . . . He then carefully unfolded a slip of paper, which contained three or four lines of characters, as unlike letters or hieroglyphics of any sort, as well could be produced were one to shut up his eyes and play off the most antic movements with his pen upon paper.

According to the Fayette Lapham article that appeared in the Historical Magazine in May 1870, Martin Harris also showed the characters to George Crane—

Joseph [Smith], not being able to read the characters, made a copy of some of them, which he showed to some of the most learned men of the vicinity. All the clue he could obtain was fromGeorge Crane, who said he had seen a Pass that had been given to Luther Bradish, when traveling through the Turkish dominions; and he thought the characters resembled those of that Pass.[12]

A “Pass” is like a passport. Luther Bradish, a student of languages and a traveler in the Middle East, apparently showed his “Pass” to George Crane as verification of his travels.

Pomeroy Tucker wrote that Martin Harris sought the interpretation of the characters from “such scholars as Hon. Luther Bradish.”[13] It is presumed that Martin Harris showed the characters to Luther Bradish in February 1828 in Albany while on his way to New York City.[14] It is also presumed that Luther Bradish suggested that Martin meet with Dr. Samuel Latham Mitchill M.D., vice president of Rutgers Medical College, and Charles Anthon, professor of classical studies at Columbia College.[1]

Returning to Palmyra after meeting with these scholars, Martin Harris again approached Reverend John Clark about the characters. Reverend Clark wrote, “He came to see me again, and told me that, among others, he had consulted Professor Anthon, who thought the characters in which the book was written very remarkable, but he could not decide exactly what language they belonged to.”[15]

Four months after Martin Harris had shown Bradish, Anthon, and Mitchill the Egyptian characters, Martin finished scribing the 116 page manuscript. On June 14, 1828, Martin carried the 116 pages to Palmyra. He had the manuscript in his possession for three weeks—until about July 7, 1828. During those weeks, Martin showed the manuscript to any “prudent” person who visited him. Luther was interested in antiquities and early American writings—so, if Luther had said the manuscript had been taken from an ancient document, it would have given authenticity and credibility to the work of Joseph Smith and Martin Harris.

The question is, was Luther Bradish in Palmyra in July 1828? Let us reason together. The New York legislature would not have been meeting in July, so Luther would not have needed to be in Albany during that time. His extended family was living in Palmyra, including his widowed mother. His mother might have been ill in July 1828, for she died in December 1828.

Consider the following scenario as a conspiracy by using people named by Fayette Lapham in the 1870 article. George Crane was the leading elder of the Quakers in the area. He lived near Calvin Bradish, brother of Luther Bradish. According to Fayette Lapham, George Crane “had seen a Pass that had been given to Luther Bradish.” This suggests that George Crane met Luther Bradish. Luther knew how to get something published. He played a mediating role between author James Fenimore Cooper and publishers Isaac Carey and Isaac Lea of Philadelphia. John Clark was the reverend of Calvin Bradish, and knew men that were “too wily thus to be caught.”

Lieutenant Governor

Luther attended the National Republican Convention as a delegate from Moira, Franklin County.[16] He was “nominated by the anti-masons and National Republicans, as a candidate for congress, to represent the district composed of the counties of St. Lawrence and Franklin.”[17] Although his election seemed sure, Luther only received 2,718 votes in St. Lawrence and 1,099 votes in Franklin in November 1832. His opponent, Ransom H. Gillett, won by 80 votes.[18]

Luther Bradish again threw his hat in the political arena. He won reelection to the New York Assembly and served from 1836 to 1838. During this legislative term, he was elected Speaker of the House. He was asked to serve on the board of the United States Bank, even though he was accused by the editor of the Wayne Sentinel of belonging to “a desperate band of speculators, whose political and private fortunes depend upon the favor of Mr. Biddle and his bank.”[19]

In 1838, Luther ran as a Whig candidate for lieutenant governor of New York. This was at a time when abolitionism in the state of New York was a growing political force. Its activists posed three questions to candidates for state positions: 1) the right of blacks to a jury trial when seized as fugitive slaves, 2) a law freeing slaves-in-transit the moment they were brought into the state by their masters, and 3) equal suffrage for freed slaves. Due to his support for the three questions posed, Luther Bradish was endorsed by abolitionists.

He was elected lieutenant governor of New York in 1838, serving from 1839 to 1842 with William Seward as governor. When Governor Seward declined to run for re-election in 1842, Luther ran for the office. He was defeated by Democrat William C. Bouck.

A Recognized Leader to the End

In the later years of his life, Luther was appointed US assistant treasurer for the state of New York, and elected president of the American Bible Society as well as president of the New York Historical Association.

By 1850, Luther was residing in the New York City 18th Ward with his third wife, Mary Eliza Hart.[20] In 1855, Williams College conferred upon him the honorary degree of LL.D.

Death of Luther Bradish

Luther died on August 30, 1863 at the Ocean House Hotel in Newport, Rhode Island.[21] His body was returned to New York City and buried in the Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, Kings County, New York.

Luther Bradish’s Timeline

April 15, 1783: Born in Cummington, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, to Colonel John Bradish Jr. and Hannah B. Warner.

1803: Attends Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Writes letters to his parents detailing his college experiences and reflections on growing up.

1804: Graduates from Williams College and briefly works as a teacher before entering the legal profession.

1812: Volunteers for service in the War of 1812, interrupting his law practice.

April 21, 1814: Marries Helen Elizabeth Gibbs in Cummington. Helen dies in 1816 from complications related to childbirth along with their stillborn son.

1816: Marries Lucy Abigail Durkee in St. Lawrence, New York.

1819: Commissioned by U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams as a special envoy to negotiate a treaty with the Ottoman Empire concerning Mediterranean commerce and shipping. Serves in this capacity until 1825 but fails to secure a treaty.

1819-1825: Travels extensively in Europe and the Middle East, learning Arabic and German and studying the region’s languages, manners, and antiquities. Also becomes involved in trafficking Egyptian artifacts.

Late 1820s: Returns to the United States, settles in Moira, New York, purchasing large tracts of land and becoming a prominent citizen. He mediates between James Fenimore Cooper and publishers in Philadelphia.

1827: Mentioned in the Geneva Palladium having letters at the post office in Geneva, NY. Begins political career, representing Franklin County in the New York State Legislature from 1828 to 1830. Advocates for canals and other internal improvements.

Early 1830s: Continues to engage in legal and political activities, including serving in the state legislature and as Speaker of the House.

1838: Runs as a Whig candidate and is elected Lieutenant Governor of New York, serving from 1839 to 1842 alongside Governor William Seward.

1842: Runs for Governor of New York but is defeated by Democrat William C. Bouck.

Later Years: Serves as US assistant treasurer for New York and holds presidencies at the American Bible Society and the New York Historical Association.

August 30, 1863: Dies at the Ocean House Hotel in Newport, Rhode Island. Buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

Children of Luther and Mary Bradish

1. Zenas D. Bradish (1819–1872).

2. Nancy D. Bradish (1822).

3. Mary Mariah Bradish (1823–1895).

4. Jay Durkee Bradish (1826–1898).

5. Mary Hart Bradish.

6. (Child) Bradish

[1] David Kaser, Messrs. Carey and Lea of Philadelphia: A Study in the History of the Book Trade (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press).

[2] H. C. Carey to Luther Bradish, July 15, 1826, Luther Bradish Papers. Bradish and Cooper had actually known each other for several years. See James F. Cooper to Richard Cooper, May 25, 1831, in James Franklin Beard, ed., The Letters and Journals of James Fenimore Cooper 6 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960), 2:88.

[3] Luther Bradish to Messrs. Carey and Lea, April 30, 1827, Luther Bradish Papers. The amount was later raised to $5,000.

[4] Geneva Gazette and Mercantile Advertiser, December 23, 1829.

[5] “Albany, New York” and “Caractors” in Joseph Smith History, vol. A-1, p. 9. Joseph Smith Papers.

[6] Geneva Gazette and Mercantile Advertiser, January 20, 1830.

[7] Stanley Kimball, “The Anthon Transcript: People, Primary Sources, and Problems,” BYU Studies 10, no. 3 (Spring 1970), pp. 328–330.

[8] George E. Pomeroy to Luther Bradish, May 15, 1846, in Luther Bradish Papers in the New York Historical Society, New York City, NY.

[9] Philip Grandin to Luther Bradish, April 1829, in New York Historical Society, New York City, NY.

[10] JS–History 1:62.

[11] Lavina Fielding Anderson, Lucy’s Book: A Critical Edition of Lucy Mack Smith’s Family Memoir (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2001), p. 402.

[12] Fayette Lapham Esq., “Interview with the Father of Joseph Smith, Historical Magazine, May 1870, p. 307.

[13] Tucker, Origin, Rise, and Progress of Mormonism, p. 42.

[14] Tucker, Origin, Rise and Progress of Mormonism, pp. 41–42; Dan Vogel, ed., Early Mormon Documents 5 vols. (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1996), 2:546–547.

[15] John A. Clark, Gleanings by the Way (Philadelphia: W. J. and J. K. Simon; NY: Robert Carter, 1842), p. 229.

[16] Auburn Free Press, January 4, 1832.

[17] Geneva Courier, September 12, 1832.

[18] Geneva Gazette and Mercantile Advertiser, December 19, 1832.

[19] Wayne Sentinel, October 12, 1838.

[20]US Federal Census, 1850.

[21] Rhode Island Deaths and Burials 1802–1950; Obituary in the New York Herald, September 2, 1863.