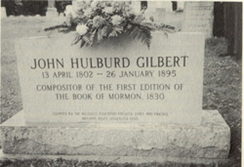

John H. Gilbert was born on April 13, 1802 inRichmond, Ontario County, New York. He was the only son of Russell Gilbert and Mrs. Hurlburd Gilbert. His middle name was his mother’s maiden name. John’s father wrote an entry in the family bible about the birth of his son: “April 13, 1802—son b.”[1]

John’s mother died when he was six months old. He was reared by his father, who was a businessman in Lavonia and a member of the Masonic Lodge in Richmond, thirty miles from Palmyra. John received a rudimentary education before his father died when he was age twelve. Seeking to find his own way, John left Richmond and ventured to Canandaigua, about eighteen miles from Palmyra. In his satchel, he carried an old violin.

At age sixteen, John learned the printer’s trade at the Canandaigua Repository. After completing his apprenticeship, he secured employment in Albany and Lewiston, New York, before moving to Palmyra at age twenty-two. He found work at the Wayne Sentinel, a newspaper owned and operated by Pomeroy Tucker. John worked as a typesetter and compositor for Tucker until purchasing the paper. Within a short time of his purchase, John sold the Wayne Sentinel on April 13, 1827 to twenty-two year old E. B. Grandin. He stayed on as Grandin’s employee. He preferred being an employee to the financial and emotional stress of being an owner. Gilbert worked as a typesetter most of his life. After he retired, John visited a printer in Palmyra every April 13th (his birthday) to set a stick of type and “to show the boys how the old man did it,” and tell them jokes of his early career as a printer.

To supplement his income, John was a “dancing-master”—meaning he taught dancing. He had the reputation in Palmyra of being an expert violinist and enjoyed playing for young people. He was also employed as a toll collector at the Thomas Rogers II Basin on the Erie Canal.[2] All boats (packets) passing through Palmyra were expected to stop at the basin. Captains were to give the name of their boat, and get a clearance. When the packet approached the basin, a trumpet blared to alert townsfolk. Horses were sent in a fast trot to draw the boat to the landing. In the year 1827 alone, the Canal Commission reported the toll collected in Palmyra was $84,009.96. The collector’s salary was $1,000 annually. When John quit his work as a toll collector in 1842, Pomeroy Tucker took his place.

John, as required by every adult male age eighteen to forty-five in Palmyra, joined the New York Ontario County Militia. There is no record of his having fought in any skirmish. It was said that he got the title “Major John H. Gilbert” because he commanded a company of militiamen who trained on Gate Street near his home in Palmyra. Historical evidence does not support this claim. It appears the title of Major was honorific.

At age twenty-five, John married Chloe Priscilla Thayer (1811–1889) on September 4, 1827 in the Zion Episcopal Church in Palmyra.[3] (At the time, the Zion Episcopal Church was under the direction of Reverend John A. Clark. Although John was never a church-going man, he helped build and fund the Episcopal Church when Reverend Clark was in Palmyra.)

John and his bride honeymooned at Niagara Falls. John remembered seeing a condemned schooner sent over the falls so the owner would never be able to operate it again.

The Year 1828

John was age twenty-six when the 116 pages were stolen. Putting it in perceptive, Flanders Dyke was age twenty-nine. There is no mention in historical records of the whereabouts of John during the three weeks that Martin Harris had the manuscript in his possession (June 15–July 7, 1828). On August 23, 1828, he attended a meeting at the L. Hurd’s Eagle Hotel of the “Republican Young Men of the Town of Palmyra.” The young Republicans reported themselves as “friendly to the election of General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee for US President,” although General Jackson ran for president as a Democrat.[4]

In the fall of 1828, Philip Grandin, the older brother of E. B. Grandin, and Levi and Joel Thayer—Joel Thayer being the brother-in-law of John H. Gilbert—completed construction of a row of commercial stores on Main Street in Palmyra. In October 1828, E. B. Grandin moved his newspaper business into the Thayer & Grandin Row (today 219 Main Street).[5] John moved with the newspaper business as a valued employee.

Typesetter and Compositor of the Book of Mormon

In June 1829, E. B. Grandin asked John H. Gilbert to assist in printing 5,000 copies of the Book of Mormon. John became the chief compositor and typesetter of the Book of Mormon. According to him, the original printer’s copy of the Book of Mormon consisted of one solid paragraph from beginning to end. Hyrum Smith and Martin Harris brought the manuscript pages into the print shop each day and took them back for safe keeping each night. John was allowed to take the pages home to mark punctuation, but was told to leave any grammatical errors as they were.

John H. Gilbert gained Prominence for his role in printing the Book of Mormon

John H. Gilbert received little notoriety throughout his life. When he changed his political allegiance to the Democratic Party, few seemed to care. In spite of having no inclination towards religion, John came up with a religious theory on August 14, 1837—“The weeping willow originally came from Babylon! & is the same kind that the Jewish captives hung their Harps upon when the Babylonians required of them a song.”[6] John was never a wheeler or dealer in Palmyra, nor was he a man of wealth. With one exception, he never bought or sold property.[7] At a Palmyra town meeting in 1854, he was appointed inspector of elections in District No. 1. He was appointed to the same position in 1863.

John H. Gilbert eventually gained notoriety for his role in the publication of the Book of Mormon. In the late 1870s, James T. Cobb of Salt Lake City visited Palmyra to collect information about Mormon origins for a book he planned to write. On May 2, 1879, Cobb interviewed Abel Chase, a brother of Willard Chase. Chase feigned ignorance about Joseph Smith, Martin Harris, and the coming forth of the Book of Mormon. Chase told Cobb, “Don’t know anything about it but what I have heard. If you will see Mr. Guilbert [Gilbert] at Palmyra, he can tell you more about it than any person; he knows it all, and has been getting everything he could for years to publish against them; he was in with [Pomeroy] Tucker in getting out Tucker’s work.”[8] John H. Gilbert wrote to James T. Cobb in October 1879 about what Lorenzo Saunders had said regarding Sidney Rigdon. Lorenzo claimed that “Rigdon was hanging around [the] Smiths for eighteen months prior to the publishing of the Mormon Bible.”

In 1881, John H. Gilbert was interviewed by William Kelley, an apostle in the Reorganized Church, and his brother Edmund Kelley, a counselor in the Reorganized presiding bishopric. In their published account of the interview, an issue was raised about Lorenzo Saunders and what he remembered about Sidney Rigdon. John charged the Kelleys with misrepresenting and changing Lorenzo’s statement.[9] In a letter to Thomas Gregg in June 1881, John penned, “The long paragraph in relation to Mr. Cobb and Lorenzo Saunders is a mixed mess of truth and falsehood. When I asked Mr. S[aunders] if he knew whether Rigdon was hanging around Smith previous to the publication of the M. B. [Mormon Bible], he said, “Yes, at least eighteen months before. There was no hesitancy about it; and this is what I told Kelley. You can see how he reported the matter.”[10]

In 1881, Edmund Kelley also interviewed Abel Chase. In the interview, Abel provided testimony in support of the Peter Ingersoll Affidavit in Mormonism Unvailed: “I certify that I have been personally acquainted with Peter Ingersoll for a number of years, and believe him to be a man of strict integrity, truth and veracity.” [11] Abel also claimed that the affidavit of his brother Willard Chase in Mormonism Unvailed was “genuine.” Abel signed his statement in the presence of Pliny T. Sexton and John H. Gilbert. They both swore that Abel Chase was “a man whose word is always the exact truth and above any possible suspicion.”[12] For unknown reasons, James T. Cobb never published his collected statements.

In September 1888, John H. Gilbert was interviewed by Joseph S. Black, Andrew Jenson, and Edward Stevenson. Joseph S. Black wrote in his journal of the interview—

We arrived at Palmyra. New York on September 27th at 4:00 p.m. This is a nice place; population of about 3.000. The main street runs east and west and is 8 rods wide, with beautiful shade trees on each side. The cross streets are 4 rods wide, We had an interview with Mr. Ford, who was well acquainted with Joseph Smith and family, when Joseph was a boy. He told us many ridiculous stories about the family. but being questioned he finally admitted that he knew nothing bad about them except what he had heard. We next visited John S. Gilbert. the man who printed the first Book of Mormon, He and his wife received us kindly. He is well preserved and hearty and is 86 years old. He answered questions frankly. We asked him what denomination he belonged to; he answered. “None.” He said we could record him as a Christian. He answered. “Not by a damsite, I do not believe in Joseph Smith. God nor the Bible.” However, he stated that he wanted to live right and would risk the future. He had kept one of the first editions of the Book of Mormon and had recently sold it for $500. He said David Whitmer had made statements in the book which were not true. He represented that they were short of means and that they wanted to sell the manuscript, which was not so, as the pay was all arranged for before the printing was commenced. He was questioned in regards to the manuscript from which the book was printed and he said they set it up in sticks and cut the manuscript in places and also made marks where they wrapped, which corresponded with the manuscript we had seen at Whitmer’s in Missouri. The one in Whitmer’s possession had the signatures all in one handwriting, while the original was signed by the witnesses in their own handwriting.

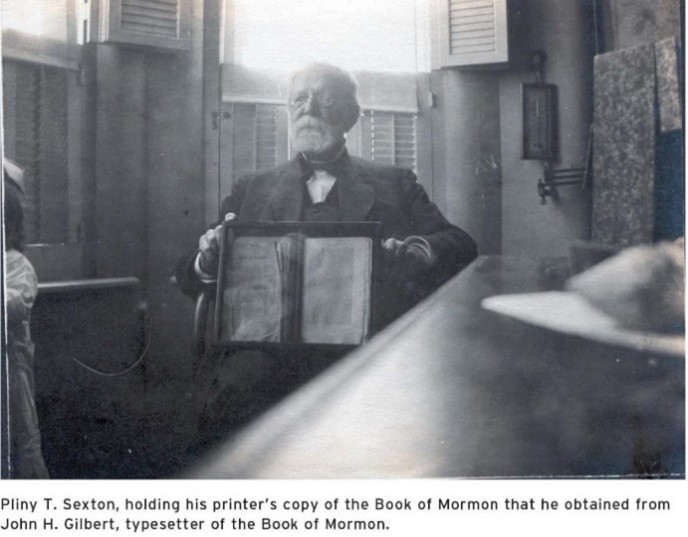

John H. Gilbert and Pliny T. Sexton

In the article “Book of Mormon” printed in the Syracuse Morning Standard on December 13, 1877 is the statement: “It was the custom of the printers, as the sheets were run through the press, to take one of each form for preservation. Gilbert had in his possession a complete copy of the book [of Mormon] in the original sheets as laid off by him from the press.” For years, he “cheerfully exhibit[ed the sheets] to any person who has a curiosity to look at them.”

As time passed, John H. Gilbert was anxious to sell his unbound copy of the Book of Mormon for no less than $500. He sold the unbound copy of the “true” sheets to Pliny T. Sexton, who also claimed to possess the first Mormon Bible ever printed. Pliny T. Sexton claimed that he acquired the proof sheets from John Gilbert as a “payment of debt,” which suggests that John did not receive the $500 payment he desired.[13]

An heir of Pliny T. Sexton sold the proof sheets to Wilford C. Wood, a collector of Mormon artifacts and documents.[14] The sheets were later donated to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by the Wilford C. Wood heirs.[15]

Preparations for “The Mormon Exhibit” at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago

John H. Gilbert’s wife, Chloe P. Thayer Gilbert, died on March 12, 1889 after sixty-two years of marriage. John survived his wife by six years. His oldest daughter, Sarah Gilbert, cared for him in his declining years. Despite declining physical health, John’s memory was clear throughout old age.

The Mormon Exhibit at the 1893 Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, marked a dramatic reengagement of the Church with the non‐Mormon world after decades of seclusion in the Great Basin. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir participated in the World’s Fair. There was also “an impressive exhibit hall.” When plans were being made for the Exhibit Hall, John H. Gilbert was asked to write his remembrance of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon.

Although John’s remembrance is fairly lengthy, we have included it in its entirety with few editorial comments. Notice the direct quotes of his which evidence he had been collecting anti-Mormon statements—

Memorandum, made by John H. Gilbert, Esq.,

Sept. 8th, 1892, Palmyra, N.Y.

I am a practical printer by trade. I have been a resident of Palmyra, N.Y., since about the year 1824, and during all that time have done some type-setting each year. I was aged ninety years on the 13th day of April 1892, and on that day I went to the office of the Palmyra Courier and set a stick-full of type.

My recollection of past events, and especially of the matter connected with the printing of the “Mormon Bible” is very accurate and faithful, and I have made the following memorandum at request, to accompany the photographs of “Mormon Hill,” which have been made for the purpose of exhibits at the World’s Fair in 1893.

In 1893, John H. Gilbert, Orson Saunders, and a reporter from the New York Herald climbed “Mormon Hill” and went to the cave. They reported, “The door jambs leading into the cave are still sound and partly visible, but the earth has been washed down by storms and the opening to the cave nearly filled, so that it cannot be entered at present. . . . The door jamb is a heavy plank of beech or maple, and the inscriptions, which had evidently been cut deeply by a sharp knife, were partially worn away.”[16] Orson Saunders made photographs of “Mormon Hill” for the Exhibit Hall at the World’s Fair.

In the forepart of June 1829, Mr. E. B. Grandin, the printer of the “Wayne Sentinel,” came to me and said he wanted I should assist him in estimating the cost of printing 5000 copies of a book that Martin Harris wanted to get printed, which he called the “Mormon Bible.”

It was the second application—Harris assured Grandin to do the job—Harris assuring Grandin that the book would be printed in Rochester if he declined the job again.

Harris proposed to have Grandin do the job, if he would, as it would be quite expensive to keep a man in Rochester during the printing of the book, who would have to visit Palmyra two or three times a week for manuscript, &c. Mr. Grandin consented to do the job if his terms were accepted.

A few pages of the manuscript were submitted as a specimen of the whole, and it was said there would be about 500 pages.

The size of the page was agreed upon, and an estimate of the number of ems in a page, which would be 1000, and that a page of manuscript would make more than a page of printed matter, which proved to be correct.

The contract was to print and bind with leather, 5000 copies for $3,000. Mr. Grandin got a new font of Small Pica, on which the body of the work was printed. When the printer was ready to commence work, Harris was notified, and Hyrum Smith brought the first installment of manuscript, of 24 pages, closely written on common foolscap paper—he had it under his vest and coat closely buttoned over it. At night Smith came and got the manuscript, and with the same precaution carried it away. The next morning with the same watchfulness, he brought it again, and at night took it away. This was kept up for several days. The title page was first set up, and after proof was read and corrected, several copies were printed for Harris and his friends. On the second day—Harris and Smith being in the office—I called their attention to a grammatical error, and asked whether I should correct it? Harris consulted with Smith a short time, and turned to me and said: “The Old Testament is ungrammatical, set it as it is written.”

After working a few days, I said to Smith on his handing me the manuscript in the morning; “Mr. Smith, if you would leave this manuscript with me, I would take it home with me at night and read and punctuate it.” His reply was, “We are commanded not to leave it.” A few mornings after this, when Smith handed me the manuscript, he said to me:—

“If you will give your word that this manuscript shall be returned to us when you get through with it, I will leave it with you.” I assured Smith that it should be returned all right when I got through with it. For two or three nights I took it home with me and read it, and punctuated it with a lead pencil. This will account for the punctuation marks in pencil, which is referred to in the Mormon Report, an extract from which will be found below.

Martin Harris, Hyrum Smith and Oliver Cowdery were very frequent visitors to the office during the printing of the Mormon Bible. The manuscript was supposed to be in the handwriting of Cowdery. Every Chapter, if I remember correctly, was one solid paragraph, without a punctuation mark, from beginning to end.

Names of persons and places were generally capitalized, but sentences had no end. The character or short &, was used almost invariably where the word and, occurred, except at the end of a chapter. I punctuated it to make it read as I supposed the Author intended, and but very little punctuation was altered in proof-reading. The Bible was printed 16 pages at a time, so that one sheet of paper made two copies of 16 pages each, requiring 2500 sheets of paper for each form of 16 pages. There were 37 forms of 16 pages each,—570 pages in all.

The work was commenced in August 1829, and finished in March 1830,—seven months. Mr. J. H. Bortles and myself done the press work until December taking nearly three days to each form.

In December Mr. Grandin hired a journeyman pressman, Thomas McAuley, or “Whistling Tom,” as he was called in the office, and he and Bortles did the balance of the press-work. The Bible was printed on a “Smith” Press, single pull, and old fashioned “Balls” or “Niggerheads” were used—composition rollers not having come into use in small printing offices.

There is a relationship between Mr. J. H. Bortles and Fayette Lapham. Fayette married Sophia B. Bortles on May 11, 1828 in Perinton, New York. Is it a coincidence that Sophia’s cousin, Jacob H. Bortles, worked with John H. Gilbert in the Grandin Press?

The printing was done in the third story of the west end of “Exchange Row,” and the binding by Mr. [Luther] Howard, in the second story[,] the lower story being used as a book store, by Mr. Grandin, and now—1892—by Mr. M. Story as a dry-goods store.

Cowdery held and looked over the manuscript when most of the proofs were read. Martin Harris once or twice, and Hyrum Smith once. Grandin supposing these men could read their own writing as well, if not better, than any one else; and if there are any discrepancies between the Palmyra edition and the manuscript these men should be held responsible.

Joseph Smith, Jr. had nothing to do whatever with the printing or furnishing copy for the printers, being but once in the office during the printing of the Bible, and then not over 15 or 20 minutes.

Hyrum Smith was a common laborer, and worked for any one as he was called on. Cowdery taught school winters—so it was said—but what he done summers, I do not know. Martin Harris was a farmer, owning a good farm, of about 150 acres, about a mile north of Palmyra village, and had money at interest. Martin,—as every body called him,—was considered by his neighbors a very honest man; but on the subject of Mormonism, he was said to be crazy. Martin was the main spoke in the wheel of Mormonism in its start in Palmyra, and I may say, the only spoke. In the fall of 1827, he told us what wonderful discoveries Jo Smith had made, and of his finding plates in a hill in the town of Manchester, (three miles south of Palmyra,)—also found with the plates a large pair of spectacles, by putting which on his nose and looking at the plates, the spectacles turned the hyroglyphics into good English. The question might be asked here whether Jo or the spectacles was the translator?

Sometime in 1828, Martin Harris, who had been furnished by someone with what he said was a fac-simile of the hyroglyphics of one of the plates, started for New York. On his way he stopped at Albany and called on Lt. Gov. Bradish,—with what success I do not know. He proceeded to New York, and called on Prof. C. Anthon, made known his business and presented his hyroglyphics.

The paper in question was, in fact, a singular scroll. It consisted of all kinds of singular characters, disposed in columns, and had evidently been prepared by some person who had before him at the time a book containing various alphabets; Greek and Hebrew letters, crosses and flourishes, Roman letters inverted or placed sidewise [sideways], arranged and placed in perpendicular columns, and the whole ended in a rude delineation of a circle, divided into various compartments, arched with various strange marks, and evidently copied after the Mexican Calendar, given by Humboldt, but copied in such a way as not to betray the source whence it was derived. I am thus particular as to the contents of the paper, inasmuch as I have frequently conversed with my friends on the subject since the Mormon excitement began, and well remembered that the paper contained anything else but “Egyptian Hyroglyphics.”

Martin returned from his trip east satisfied that “Joseph” was a “little smarter than Prof. Anthon.”

Martin was something of a prophet:—He frequently said that “Jackson would be the last president that we would have; and that all persons who did not embrace Mormonism in two years would be stricken off the face of the earth.” He said that Palmyra was to be the New Jerusalem, and that her streets were to be paved with gold.

Martin was in the office when I finished setting up the testimony of the three witnesses,—(Harris—Cowdery and Whitmer) I said to him,—“Martin, did you see those plates with your naked eyes?” Martin looked down for an instant, raised his eyes up, and said, “No, I saw them with a spiritual eye.”

Death at age Ninety-two

In 1895, at age ninety-two, artist E. J. Read painted John H. Gilbert’s portrait. The portrait is displayed in the Grandin Building in Palmyra.[17]

On January 26, 1895, John Gilbert died from a stroke of paralysis at age ninety-two in his home on Gates Street in Palmyra. His passing was calm and devoid of pain. At the time of his death, he was the oldest printer in the state of New York. His funeral was held on January 29, 1895 in the Zion Episcopal Church. Reverend Leonard Woods Richardson, rector of the Zion Episcopal Church, officiated. In attendance were four of John H. Gilbert’s children. His son William Gilbert was unable to attend the funeral due to being an invalid.

John was buried in the southeast corner of Section N, Lot 319 in the Palmyra City Cemetery. He was buried on the same corner as his wife Chloe, six of his children, and three of his grandchildren. A new headstone was placed on John’s burial site. Larry C. Porter, professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University, dedicated the site. In his dedicatory prayer, Porter said,

Our father which art in Heaven, as a bearer of the holy Melchizedek Priesthood and in the name of Jesus Christ, I dedicate this plot of ground . . . we pray that this special lot, lot 319, will, in the morning of the resurrection, be a special and hallowed spot for John Gilbert, his wife, and his loved ones. We pray, our Father in Heaven, that thou wilt bless his memory and bless his spirit for his contribution and the aid, the help which he has given to the Latter-day Saint people.

A Curiosity

In 1980, when restoring the Grandin Building, Church Historic Site personnel crawled into the attic for a cursory look around. At first, they believed it was empty except for a large uninhabited wasps’ nest and a thick layer of dust. Then they noticed a piece of paper which was stuck to the plaster between the beams. It was a newspaper fragment from 1828. Looking further, they not only found more newspaper scraps, but actual letters as well—a letter to Pomeroy Tucker, who was an editor of the Sentinel and the author of an antagonistic history of the rise of Mormonism. The Historic Site personnel also found another letter addressed to Pomeroy Tucker and his partner, John H. Gilbert.[18]

Children of John and Chloe Gilbert

1) Sarah Eliza Gilbert (June 26, 1828–November 20, 1910). She resided in Palmyra from 1850 to 1880, and in Detroit from 1900 to 1910.

2) John Hurlburd Gilbert Jr. (October 26, 1829–May 27, 1865).

3) Frances A. Gilbert (February 25, 1831–September 6, 1834).

4) Ruth Thayer Gilbert (February 14, 1833–January 14, 1834).

5) Julia May Gilbert (December 20, 1834).

6) William S. Gilbert (July 4, 1837–March 29, 1905).

7) Mary J. Gilbert (December 6, 1839–April 27, 1845).

8) Charles T. Gilbert (March 12, 1842–November 2, 1900). He married Celestia Priest (1843–1926). He resided in Palmyra from 1850 to 1860, and was residing in Detroit in 1870, where he was a successful businessman.

9) Belle Gilbert (1844). She resided in New York City in the 1890s.

10) Joel N. Gilbert (November 25, 1844–June 8, 1845).

11) Mary Jane Gilbert (June 12, 1845).

12) Joseph A. Gilbert (November 25, 1849–September 5, 1850).

13) Isabell Robinson Gilbert (December 21, 1852–October 21, 1928). She married John C. Williams on November 16, 1875 in the Zion Episcopal Church in Palmyra. She resided in New York City in the 1890s.

[1] Russell Gilbert Family Bible.

[2] Frederick G. Mather, “The Early Days of Mormonism,” Lippincott’s Magazine [Philadelphia], August 1880, pp. 198–206, 211.

[3] Marriages recorded in the Zion Episcopal Church of Palmyra.

[4] “Young Men’s Meeting,” Wayne Sentinel, August 22, 1828.

[5] “Published every Friday Morning, by E. B. Grandin,” Wayne Sentinel, October 19, 1827.

[6] Mary Durfee Diary, in Wayne County Historian’s Office.

[7] Ontario County, NY Grantee Deed Index, 1789–1845.

[8] Von Wymetal, Joseph Smith, the Prophet, pp. 230–231. “William H. Kelley, “The Hill Cumorah, and the Book of Mormon,” Saints’ Herald 28 (June 1, 1881), p. 165.

[9] John H. Gilbert Letter to James T. Cobb, February 10, 1879 addressed to Salt Lake City, Utah Territory.

[10] John H. Gilbert Letter to Thomas Gregg, 1881.

[11] Von Wymetal, Joseph Smith, the Prophet, pp. 230–231; William H. Kelley, “The Hill Cumorah, and the Book of Mormon,” Saints’ Herald 28 (June 1, 1881), p. 165.

[12] Abel Chase Interview with E. L. Kelley, in Von Wymetal, Joseph Smith, the Prophet, pp. 230–231.

[13] Union and Advertiser, January 27, 1895.

[14] Wilford C. Wood, Joseph Smith begins His Work: Book of Mormon 1830 First Edition, Reproduced from Cut Sheets (Salt Lake City: Wilford C. Wood, 1958).

[15] Troskosky, Palmyra: A Bicentennial, pp. 126, 167; Cook, Palmyra and Vicinity, p. 89.

[16] New York Herald, June 25, 1893.

[17] Bonnie Hayes, Historian, in Palmyra History Museum, January 18, 2019.

[18] “Historic Discoveries at the Grandin Building,” Ensign, July 1980.