John Alonzo Clark, son of John Clark and Chloe Atwater, was born on May 6, 1801 in Pittsfield, Berkshire County, Massachusetts. At the time of John’s birth, there were approximately 2,200 residents in Pittsfield. Most of the residents worked in milling. With the introduction of Merino sheep from Spain in 1807, Pittsfield became the center of woolen manufacturing in the United States, an industry that dominated the community’s economy for almost a century.

John’s recollections of childhood included early memories of walking with his sister to the country schoolhouse and gathering flowers that grew along the green bank of the Housatonic River.[1] He also recalled being sickly, having inherited his mother’s delicate constitution. He suffered from marasmus, which comes from a Greek word that means “withering,” and had malnutrition which led to a deficiency in energy—yet his childhood dream was to one day be like his father and grandfather who fought in the American Revolutionary War. His father fought in the Battle of Oriskany in New York.[2]

At age fifteen, John was living with his family in Manlius, Onondaga County, New York, the largest trade center in the area. It was not trade or the bustling community that captured his fancy, however. John had a religious bent—a concern for “personal salvation.” Recognizing his spiritual yearnings, Bishop John Henry Hobart (1775–1830) guided him toward a career in the Christian ministry.

The Influence of Bishop John Henry Hobart

No single man was more influential in the life of John Clark and his brothers William and Orin Clark than Bishop John Henry Hobart (1775–1830). Bishop Hobart was the third Episcopal bishop of the state of New York, serving from 1816 to 1830. In 1818, Hobart became convinced that a seminary of higher education was needed in Western New York. He set up his institution of learning in the small village of Geneva on Seneca Lake. In 1822, as the Clark family moved into their “paternal mansion” in the village, Geneva College was beginning to admit students.

John did not initially enroll in the Geneva College. Instead, he entered the junior class of Union College near Albany in 1821 and graduated in July 1823. He and his brothers then enrolled in the Geneva College, studying theology under the tutelage of Reverend Dr. McDonald, an appointee of Bishop Hobart. Of attending college in Geneva, John later penned, “There is not a lovelier spot beneath the far-expanded sky for the site of a village than the banks of the Seneca.” He referred to Geneva as “The Gem of Western New York.”[3]

John Stafford of Palmyra, who later reported seeing the Smiths digging for treasure in Manchester/Palmyra, said that “he knew the Smith family well, and was present at the first baptism, when old Granny Smith and Sally Rockwell were ‘dipped’ and came up ‘white as snow.’” Spafford also attended the Hobart College in Geneva.

John Clark continued his studies at the General Theological Seminary in New York City, another institution of learning founded by Bishop Hobart.[4] On April 12, 1826, he was ordained a deacon and admitted into the “Order of the Episcopal Church” at the All Saints Church in New York City, where his brother William Clark served as rector.[5]

Marriage

At age twenty-three, John married Sarah Buell on March 28, 1824. They were married in the First United Methodist Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Sarah was born in Fairfield, Herkimer County, New York, a village named after Fairfield, Connecticut and located east of Utica. She was an educated young woman, having taken advantage of the educational opportunities offered at the Fairfield Academy.

There is historic conjecture over the number of children born to John and Sarah Clark. Some historians claim nine children were born, with six dying in infancy. Other historians claim eleven children were born, with ten dying before adulthood. Either way, John and Sarah had great heartache over the deaths of their infant children.

In 1826 John comes to Palmyra

His professional career as a minister spanned the years of the Second Great Awakening, an evangelical movement which spread across much of the country. Although the Awakening was widespread, it was most strongly felt in the “burned-over” district of Western New York. John represented the evangelical wing of the Episcopal Church. He quickly gained a reputation as a notable and eloquent preacher. On August 14, 1826, John presided at the first organization of an Episcopal society in Lyons, New York and then over the organization of an Episcopal society in Sodus, New York. He also officiated at meetings in Geneva and Pultneyville. From 1826 to 1829, John was an Episcopal missionary called to save souls in Palmyra, Sodus, and Geneva, New York. At the time, he was described as—

slight figure, perfectly erect, and in his walk there was a firm, self-reliant bearing, which indicated a man of earnest mind and decided purpose . . . As you first looked upon his countenance, you saw nothing especially attractive in his dark complexion and the rather irregular grouping of his features; but these were lost sight of in his general expression, which revealed a spirit that had evidently been touched and molded by the divine power of Christianity, and which withal was no stranger to the gracious chastening of our Heavenly Father.[6]

In 1826, John spoke on alternate Sundays in Palmyra and Geneva. He wrote out each sermon read from the pulpit. His sermons for the years 1826 to 1843 have been compiled into twenty-nine booklets found online. They are not an exciting read, but do reflect John’s ecclesiastical emphasis on the inherent sinfulness of man, his acceptance of Christ as the Redeemer, and the necessity of conversion through faith. They also reflect John’s view on the political situation at the time, and his near reverence for Bishop Hobart.

In 1827, the number of worshippers listening to his sermons increased dramatically in Palmyra. “The regular attendants upon divine service are nearly double what they were last year when I made my report,” John wrote to his ecclesiastical superiors.[7] Noting John’s success, at the Diocesan Convention in 1827, Bishop Hobart admitted him into the “Holy Order of Priests,” which meant John was now referred to as Reverend John Clark.[8]

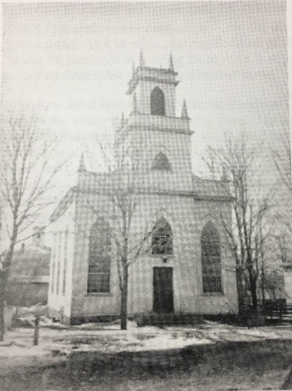

Being a reverend gave John the right to ask for subscriptions to build the Zion Episcopal Church in Palmyra. By contributing subscriptions of $25 or more, the subscriber was entitled to a pew in the church. By May 11, 1827, enough subscription monies had been collected that Reverend John Clark was able to move ahead with his plans to construct a 20,000 square-foot gothic church. A lot was purchased at 120 East Main Street in Palmyra from the estate of fifteen year old George W. Cuyler, with his step-father Thomas Baldwin negotiating the purchase price. In the property deed, the purchase price was $300 with the stipulation that Thomas Baldwin be given “life rights” to a pew in the church.

As the name of Reverend Clark became more prominent in Palmyra and throughout the county, on June 27, 1827 he was elected an honorary member of the Ontario Medical Society.[9] Membership in the that society was definitely honorific, for there is no record of Reverend Clark attending a medical college or having any interest in medicine except for issues related to his delicate constitution.

On September 28, 1827, about a week after Joseph Smith received the plates from the angel Moroni, the cornerstone of the First Zion Church was laid. The Masonic fraternity took part in laying the cornerstone. A manuscript containing the names of important people in the Zion Church (which no doubt included the names of Reverend Clark, Thomas Baldwin, and his step-son George W. Cuyler), presidents of the United States, and the Wayne Sentinel newspaper were placed inside the cornerstone. The building was completed on January 30, 1829.

Two sermons given in Palmyra by Reverend Clark have been preserved. The first was given at the pulpit of the Zion’s Episcopal Church on September 14, 1828—“God will not accept of a poor or partial offering” (Malachi 1:8). The second was given at the same pulpit in October 1828—“St. Paul’s Valedictory to the Elders at Ephesus” (Acts 20:32).[10] Reverend Clark was never known among his parishioners as a pulpit orator, but his sermons were well-written and thought provoking.

John returned to Palmyra in August 1840 and wrote, “I spent a Sabbath most delightfully at Palmyra preaching in the neat and tasteful church edifice erected there. Most deeply affecting was to see among the serious and exemplary communicants of this church, some who during my residence in that place were among the giddiest youth of the village.[11]

Reverend John Clark and Martin Harris

So great was the frenzy and mob-like atmosphere stemming from rumors about gold plates that Joseph Smith “was under the necessity” of looking beyond Palmyra for safety (JS–History 1:61). Lucy Mack Smith wrote, “Alva Hale, Joseph’s brother-in-law, came to our house from Pennsylvania, for the purpose of moving Joseph to his father-in-law’s” house in Harmony.[12] As Martin Harris was assisting Joseph in loading household goods into Alva Hale’s wagon, it was proposed that Martin come to Harmony, but give Joseph sufficient time to transcribe a few Egyptian characters from the plates. Martin was then to “take the characters to the East, and on his way, he was to call on all the professed linguists, in order to give them an opportunity to display their talents in giving a translation of the characters.”

In Harmony, Joseph “commence[d] copying the characters off the plates” in anticipation of Martin’s arrival (JS–History 1:62). Martin arrived in February 1828 and was given the characters. He returned to Palmyra and, according to Reverend John Clark, showed him the characters. Clark wrote,

Martin Harris called at my house in Palmyra, one morning about sunrise. His whole appearance indicated more than usual excitement, and he had scarcely passed the threshold of my dwelling, before he inquired whether he could see me alone, remarking that he had a matter to communicate that he wished to be strictly confidential. Previous to this, I had but very slight acquaintance with Mr. Harris. He had occasionally attended divine service in our church. I had heard him spoken of as a farmer in comfortable circumstances . . . I invited him to accompany me to my study, where, after having closed the door, he began to draw a package out of his pocket with great and manifest caution. Suddenly, however, he stopped, and wished to know if there was any possibility of our being interrupted or overheard?

When answered in the negative, he proceeded to remark that he proposed great confidence in me as a minister of Jesus Christ, and what he had now to communicate he wished me to regard as strictly confidential . . . He then carefully unfolded a slip of paper, which contained three or four lines of characters, as unlike letters or hieroglyphics of any sort, as well could be produced were one to shut up his eyes and play off the most antic movements with his pen upon paper. The only thing that bore the slightest resemblance to the letter of any language that I had ever seen, was two upright marks joined by a horizontal line, that might have been taken for the Hebrew character ח. . . . The whole thing appeared to me so ludicrous and puerile, that I could not refrain from telling Mr. Harris, that I believed it a mere hoax got up to practice upon his credulity, or an artifice to extort from him money . . . My intimations to him, in reference to the possible imposition that was being practiced upon him, however, were indignantly repelled.

When Martin Harris again approached Reverend John Clark about the characters after his return from New York City, Reverend Clark wrote, “He came to see me again, and told me that, among others, he had consulted Professor Anthon, who thought the characters in which the book was written very remarkable, but he could not decide exactly what language they belonged to.”[13]

Reverend Clark also wrote of Martin returning to Harmony, being the scribe for the Book of Lehi translation, and of the translation process—Joseph Smith was concealed behind a blanket and using spectacles. “What other measures they also took to transcribe or translate from these metallic plates, I cannot say,” wrote Reverend Clark, “as I very soon return to another field of labour for I heard no more of this matter till I learned the Book of Mormon was being published.”[14] This is not true! Reverend Clark had direct knowledge of the loss of the 116 pages and of the plates. A quote from a “Letter addressed to Dear Brethren, August 31, 1840” in The Episcopal Recorder (Philadelphia) of September 1840 and later reprinted in Gleaning by the Way appeared in the infamous CES Letter. In the quote, John Clark wrote of Martin Harris being asked, “But did you see them [plates] with your natural, your bodily eyes, just as you see this pencil-case in my hand? Now say no or yes to this.” Martin answered, “I did not see them as I do that pencil-case, yet I saw them with the eye of faith. I saw them just as distinctly as I see anything around me, though at the time they were covered over with a cloth.”

The Year 1828

On June 14, 1828, Martin Harris carried the 116 pages to Palmyra. He had the manuscript in his possession for three weeks (until about July 7, 1828). During those weeks, Martin showed the manuscript to any “prudent” person who called. Would Reverend John Clark be considered a prudent person in 1828? Yes! Martin confided in Reverend Clark in February 1828 by showing him the characters. Martin was a proud man and would want to prove to Reverend Clark the authenticity of his scribed work.

However, Reverend Clark had no criminal history. He was strictly a religious zealot. Religion wasn’t just a crutch to him, it was his livelihood—his passion. He saw his role in life as saving souls and bringing them unto Christ. Let us reason together—

Reverend John Clark penned, “Harris wrote down one hundred and sixteen pages and lost them. . . . the pages were lost in the following way”—

Harris brought home the manuscript pages and locked them in his house, thinking them quite safe. But his wife, who was not then, nor ever afterwards became a convert to Mormonism, took the opportunity, when he was out, to seize the manuscript and put it into the hands of one of her neighbours for safekeeping. When the manuscript was discovered to be missing, suspicion immediately fastened upon Mrs. Harris. She, however, refused to give any information in relation to the matter, but simply replied: “If this be a divine communication, the same being who revealed it to you can easily replace it.”

He wrote of Lucy’s scheme:

[Lucy took it] for granted that they would attempt to reproduce the part that she concealed, and that they could not possibly do it verbatim, she intended to keep the manuscript until the book was published, and then put these one hundred and sixteen pages into the hands of some one who would publish them, and show how they varied from those published in the Book of Mormon. But she had to deal with persons standing behind the scene and moving the scenery that were too wily thus to be caught.[15]

Do we think that Lucy Harris was smart enough to come up with the scheme? Is Reverend Clark referring to himself when he writes of being “too wily”? Reverend Clark is smart. He has a premier education in theology. His zealous embrace of protecting his version of Christian religion might trump his sense of honesty. Did Martin Harris show him the pages? Did he trespass into Martin’s house and steal the pages? His absence at the July 3, 1828 wedding of Polly Harris would not have been noticed. It was Reverend Blakeslee who married Polly Harris and William Parker, not Reverend Clark.

Reverend Clark goes on in his narrative to give the Doctrine and Covenants account of Joseph Smith being told not to retranslate the lost pages before making the erroneous conclusion, “Had those pages, however, been transcribed verbatim from Mr. [Solomon] Spaulding’s manuscript, they would undoubtedly have re-produced them, and urged the fact of their being able to do so as a still further proof of their divine inspiration.” Reverend Clark literally believed that the 116 pages (and, indeed, the entire Book of Mormon) was a copy of Solomon Spaulding’s manuscript.

Supporting Reverend Clark in this theory was Mrs. Davison, widow of Solomon Spaulding, and John Spaulding, brother of Solomon Spaulding.[16] As if presenting evidence that this was the case, John Clark wrote, “I have been able to lay hold of one or two valuable documents, and to obtain several items of intelligence by which I shall be able to continue this sketch of the rise and origin of this single imposture [meaning The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints].” Are these documents the statements of Mrs. Davison and John Spaulding, or did Clark have in his possession the 116 pages?

John Clark moves out of Palmyra

The official record stated, “In 1829 due to severe domestic affliction, John was forced to resign from the church.”[17] What was the domestic affliction? Is he having marital difficulties—affairs? He stays with his wife after his Palmyra years and has many more children. Reverend Clark is so concerned about salvation and calling sinners to repentance, extra-marital affairs seems unlikely. What about the deaths of his children? Is their health the domestic affliction? He has two children at the time—his oldest son was age two, and his second son was an infant. Neither child died until 1830. Events following the death of his brother, Orin Clark, on February 4, 1828 in Geneva, New York may have contributed to “the severe domestic affliction.” According to the records of the state of New York, on May 19, 1828 in Canandaigua, New York, John Clark became the legal guardian of Cornelia Ann Rutgers Clark and Eliza Clark, daughters of the late Orin Clark. Yet it does not appear that John and his wife raised his brother’s daughters.

The excuse for resigning his ecclesiastical position is weak. Years later, as his children died one after another, Reverend Clark never resigned from his position in the Episcopal Church. I don’t think resignation had anything to do with “severe domestic affliction.” In Palmyra, he was successful and respected. So, why did he leave town within six months of the loss of the 116 pages?

Although Reverend Clark left Palmyra and everything surrounding the publication of the Book of Mormon, he never left it alone. He didn’t just go about his ministry and put his days in Palmyra behind him. It isn’t the building of the beautiful gothic church that he recalled, it was Joseph Smith, Martin Harris, and the Book of Mormon.

Additional Service in the Episcopal Church

In 1829, John became an assistant to Dr. Thomas Lyell, rector of Christ Church in New York City. It was in that city that he gained a “high reputation as a preacher.”[18] In 1832, he was appointed rector of the Grace Church in Providence, Rhode Island, described as “a feeble parish of 41 communicants.” Within seven months, the number increased to fifty-seven communicants. H. B. Huntington said of Reverend Clark’s ministry in Providence, “It is doubtful if among the many remarkable men who have exercised their ministry in Grace Church there has been one of more magnetic personality than that of this pioneer, so filled was he with the zeal of the Lord and the fire of His Spirit.”[19] In spite of his frail constitution, Reverend Clark conducted weekday religious meetings in private houses called “parochial visitations.” During the visits, he sang hymns with his parishioners, prayed with them, and urged them to greater faith and repentance.[20]

A few years before his death, John visited Providence again: “The church where I once preached the reconciling word, the lecture-room where I saw countenances that called up with thrilling emotions the memory of days and scenes will be fresh in my recollection through all eternity.”[21]

A letter sent to him in Providence from his brother William Clark has been preserved—

The letter was in response to a query sent by Reverend Clark about an upcoming trip to New York City. His brother William wrote on May 6, 1835—

Yours dated yesterday is just received and I hasten to say that we shall expect you to our house to breakfast on Tuesday night; 110 15 Ridge St. near to Grand St. Why in the world you should have doubted whether we had a bed for you, I don’t know. You must explain the matter when you get here. We always have a prophet’s bed, and yet (God be Praised) a little cake to set before him, so that you need be under no apprehensions in coming straight to the house and calculating to spend your nights with us.

I have just received a letter from Mr. Gras and another form Peter dated April 30th from Geneva (New York). They were to start on the 4th – All Well –

Respects to all,

Truly Yours

William A. Clark

St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church

In 1835, Dr. H. V. D. Johns was elected to succeed the late Dr. Gregory T. Bedell as rector of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church on Eighth and above Spruce Street in Philadelphia, one of the outstanding evangelical parishes of the day. He declined the position. John Clark, a well-known and highly esteemed servant of the Lord, was invited to be the rector in his place. When John’s parishioners learned he would be leaving Providence, some were bitter. As he was entering the church to give his farewell sermon, a messenger stopped him and told him that his infant daughter was dead. The acrimonious thought and the dissatisfied word gave place to feelings of sympathy for the suffering man. The next Sunday when John delivered his parting discourse, there was no bitterness.[22]

John accepted the position of rector of the St. Andrews Episcopal Church on Eight above Spruce Street in Philadelphia and began his service on September 23, 1835, although he appeared feeble to his new parishioners.[23] In this church, a white marble tablet is hung in memory of John’s ministry and piety.

Due to a generous $55 donation from the ladies of the Grace Church in Providence, John was invited to join the American Tract Society, an organization committed to the evangelical ideal of saving souls for Christ. The goal of the society was accomplished, in part, by the distribution of religious tracts to every family in the United States within one generation, and reflected a decided millennial fervor. John received a certificate of membership in the society signed by the first president of the society, S.V.S. Wilder.

In 1835, Reverend Clark began writing tracts (books) representing the evangelical section of the Episcopal clergy. Of his writings, Bishop George Gillespie said, “The writings of Dr. Clark are among our most popular practical Church books.” The following is a list of his books. (His online books/pamphlets/sermons are available for purchase)—

Pastor’s Testimony (Philadelphia: W. Marshall & Co. (1835).

The Young Disciple; or a Memory of Anzonetta R. Peters (1836).

Gathered Fragments (1836).

Glimpses of the Old Word; or Excursions on the Continent, and in the Island of Great Britain 2 vols. (Philadelphia: W. Marshall & Co., 1840).

A Walk about Zion (New York: Robert Carter & Brothers, 1837).

Gleanings by the Way (Philadelphia: W. J. and J. KI. Simon, 1842).

The Bereaved Parent, a discourse preached in St. Andrew’s Church by John A. Clark, January 24, 1841, the third Sunday after Epiphany and Awake, Thou Sleeper (1844) Published posthumously.[24]

None could deny that Reverend Clark was a prolific writer in defending Christianity. On October 16, 1837, Bishop Hobart recognized his untiring service in the cause of Christ and his confirming of 336 persons in Philadelphia. Hobart advanced John Clark in the Episcopal priesthood.[25] Yet, there were health issues that could not be ignored. On the advice of three of Philadelphia’s most reliable physicians, Reverend Clark was given a leave of absence from the ministry. He was advised to go to Europe. It was hoped that Europe would prove the means of arresting what Reverend Clark termed his “disease.” He was granted a European sabbatical from 1837 to 1838.

In 1837, Reverend Clark was issued a passport. His passport contained a physical description of him:

Age: 36 years Stature: 5 feet 7 ¼ inches Forehead: rather high Eyes: Black Nose: straight Mouth: large Chin: round Hair: Black Complexion: dark Face: long[26]

He arrived in Liverpool aboard the Algonquin on June 16, 1837. When Reverend Clark returned from Europe, he was better but not well.[27]

In 1840, the Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio presented him with a Doctor of Divinity Degree.[28] Soon after receiving this distinction and while serving as the editor of the Episcopal Recorder in Philadelphia, John visited Palmyra in August 1840 and began writing a series of letters to the Episcopal Recorder “detailing some facts connected with the rise and origin of “Mormonism.” Of his published ten letters, only the last five talk of Mormonism.

In Gleanings by the Way (1842), Clark includes information contained in his published letters.[29]In the preface, he gives reasons for writing the book: “For several years the author has been laboring under infirm health, and has found it necessary . . . to retire from the scene of his ministerial duties, and seek to recruit his wasted strength and enfeebled health amid the retirement of rural life, or the diversified scenes of travel and journeying. During these seasons of relaxation, the author desired still to be engaged in something that might at least indirectly promote the interest of religion.”

The first 215 pages of Gleanings is about John Clark’s travels in “the Far west”—river boat excursions to Wisconsin. His journal-like descriptions of scenery are punctuated with scriptural commentary. When viewing the “savage” Native Americans, Reverend Clark laments, “Oh thought I, that they could have the gospel to tame their fierceness, soften their savage natures . . . we’re going to meet them at the judgment bar—shall we not make every effort to send them the gospel?”[30] At every stop along the river, Reverend Clark visited churches, clergymen, and graveyards. His most dramatic experience was going to the cemetery in Galena, Illinois and seeing the grave of his sister. He wept like a child.

Beginning on page 216 and extending to page 352, Reverend Clark shares his views of “Mormonism.” His views were first written in a series of letters in 1840 for the Episcopal Recorder, a religious periodical published in Philadelphia. He was an editor of the Recorder at the time. His account of the beginning of our Church is fairly accurate. It is his memory of Martin Harris in the autumn of 1827 that captured our attention. Reverend Clark presented “an outline of the principal topics contained in the Book of Mormon.” In so doing, he literally summarized the Book of Mormon beginning with the Book of Nephi, becoming the first person to publish a summary of the book. He referred to his summary as an “Analysis of the Book of Mormon.”[31] We read through his analysis to see if he introduced anything new. We found that Reverend Clark gave a correct summary, but we did not always agree with his editorial comments. He also gave an anti-Mormon view of the history of the Church from Palmyra to Missouri before returning to the subject of Martin Harris. On page 342, he included the “Statement of Lucy Harris, Wife of Martin Harris taken from Mormonism Unvailed.” Then he wrote,

There are no Mormons in Manchester, or Palmyra, the place where this Book of Mormon was pretended to be found. You might as well go down into the Crater of Vesuvius and attempt to build an ice house amid its molten and boiling lava, as to convince any inhabitant in either of these towns, that Jo Smith’s pretentions were not the most gross and egregious falsehood.[32]

Reverend Clark then writes of Lucy Harris’s failing health. How did he know that? He claims, “A gentleman of undoubted veracity in Palmyra told me.” Why would he care enough about Lucy Harris in 1836 to write about her failing health? It had been seven years since he was a resident of Palmyra. She was not one of his parishioners. She was a Quaker. John also asserted that Martin Harris attended his wife as she “was evidently sinking down to the grave” and sat with her in her room but “appeared to be very much occupied in writing. Lucy inquired about what he was writing? He replied that he was writing a letter to a female to whom he was going to be married when she was dead!”[33] This was found on page 349. The book ends on page 352. These are the last known writings of Reverend John Clark.

John C. Bennett in his History of the Saints or an Expose on Joe Smith quoted Clark as writing—

Joe Smith, who has since been the chief Prophet of the Mormons, and was one of the most prominent ostensible actors in the first scenes of this drama, belonged to a very shiftless family near Palmyra. They lived a sort of vagrant life, and were principally known as Money-Diggers. Joe, from a boy, appeared dull and utterly destitute of genius; but his father claimed for him a sort of second sight, a power to look into the depths of the earth and discover where its precious treasures were hid.

Bennet continues the quote by detailing money digging ventures in Palmyra.

Death of John Clark

On June 23, 1842, John Clark wrote his Last Will and Testament in Westmoreland, Pennsylvania, naming his wife and children as heirs.[34] Finding the marasmus “disease” again overtaking him, John resigned his position as rector of the St. Andrews Episcopal Church in Philadelphia in the spring of 1843. He died the following autumn on November 27, 1843 at his residence at 735 Sansom Street in Philadelphia at age forty-two.[35] The day before his death Reverend Thomas M. Clark, his successor, visited with him. Attending him at the time of his death was Dr. Rose of Philadelphia. Wardens of the St. Andrew’s Church made arrangements for his funeral held on November 29. Dr. Tying preached the funeral sermon.

An announcement of his death appeared in The Buffalo Commercial [Buffalo, NY], December 1, 1843. In the newspaper, John was eulogized as being “long and favorably known as one of the most esteemed divines in that city.”[36]

John was interred on December 1, 1843 in the churchyard of St. Andrews within a few feet of the vault that contains the remains of his predecessor, Reverend Gregory T. Bedell. His eight children lie beside him.[37] In the St. Andrews Church, a white marble tablet is hung in memory of his ministry and piety. In “The World One Hundred Years Ago” in The Scranton Tribune on January 8, 1901, John Alonzo Clark, referred to as an American Protestant Episcopal clergyman and author, was named as one of “the most prominent persons of the nineteenth century born in 1801.”

John’s widow continued to reside with her family at 735 Sansom Street in Philadelphia.

Children of John and Sarah Clark

1. John Alexander Clark (1827–1830).

2. William Orin Clark (1829–April 17, 1830).

3. Sarah Elizabeth Clark (March 23, 1831–February 1, 1833).

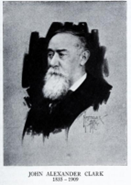

4. John Alexander Clark (April 4, 1835–May 5, 1909). He was born in Providence, Rhode Island. He was named for his uncle, the Honorable Alexander Buell, a member of the US Senate. After the death of his father, he and his mother lived at 735 Sansom Street before moving to Fairfield, New York. John returned to Philadelphia to attend school at the Episcopal Academy. He later attended Yale University before studying law at the University of Pennsylvania. In May 1856, he was admitted to the bar. John served as president of the Medical Jurisprudence Society.

He was also a vestryman in the St. Andrew’s Church. He married Eugenia Augusta Robinett on November 18, 1857 in Philadelphia.

5. Sarah Buell Clark (December 26, 1834–August 23, 1835).

6. Male Clark (1836–).

7. Mary Griswold Clark (February 5, 1836–October 17, 1836).

8. Charles Clark (April 21, 1837–March 28, 1840).

9. Charlotte Clark (April 21, 1837–March 28, 1840).

10. Charlotte Clark (December 7, 1839–June 8, 1844).

11. William Buell Clark (1840–March 30, 1852).

[1] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, pp. 111–112.

[2] Walter Herbert Stowe, Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 12, no. 4 (December 1943), pp. 267–312.

[3] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, pp. 153, 180.

[4] Stuart E. Hotchkiss, Zion Episcopal Church, Palmyra, New York: From Its Beginning to the End of the 20th Century, 2008.

[5] Hotchkiss, Zion Episcopal Church.

[6] The Reverend Francis Peck, 1857.

[7] Hotchkiss, Zion Episcopal Church.

[8] Appleton, Cyclopedia of American Biography, 1600–1889, 1:660.

[9] “The Medical Society,” Geneva Gazette and General Advertiser, June 27, 1827.

[10] The Sermons of Reverend John A. Clark are located in Special Collections at the University of Delaware.

[11] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, p. 215.

[12] Smith, Biographical Sketches of Joseph, p. 112.

[13] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, p. 229.

[14] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, p. 229.

[15] Vogel, Early Mormon Documents,2:260–261.

[16] Vogel, Early Mormon Documents,2:260–261.

[17] Hotchkiss, Zion Episcopal Church.

[18] Kathleen Burkhart, “John Alonzo Clark: From the Biography of John Clark,” posted March 11, 2013. ancestry.com

[19] A History of Grace Church, Providence, Rhode Island, 1829–1839 (Providence, RI: n. p., 1931), p. 27.

[20] Burkhart, “John Alonzo Clark.”

[21] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, p. 196.

[22] Reverend William Bacon Stevens, D. D., The Past and the Present of St. Andrews Two Discourses preached in St. Andrews Church, Philadelphia—on the 12th and 19th of September, 1858 (Philadelphia: C. Sherman and Son, 1858), pp. 25–27.

[23] Burkhart, “John Alonzo Clark.”

[24] An advertisement of his books appeared in The Keystone [Harrisburg, PA], March 6, 1841.

[25] Burkhart, “John Alonzo Clark.”

[26] John Alonzo Clark, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925.

[27] Appleton, Cyclopedia of American Biography, 1:660; Stevens, The Past and the Present of St. Andrews, p. 27.

[28] Burkhart, “John Alonzo Clark.”

[29] Appletons’ Cyclopedia of American Biography, 1600–1889, 1:660.

[30] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, p. 107.

[31] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, pp. 268–310.

[32] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, p. 348.

[33] Clark, Gleanings by the Way, p. 349.

[34] US Wills and Probate Records, 1683–1893. ancestry.com.

[35] “John Alonzo Clark: From the Biography of John Clark,” posted March 11, 2013 by Kathleen Burkhart; “Died,” The Buffalo Commercial [Buffalo, NY], December 1, 1843.

[36] “Died,” The Buffalo Commercial [Buffalo, NY], December 1, 1843.

[37] Stevens, Past and the Present of St. Andrews.