Egbert Bratt Grandin, son of William Grandin and Amy (Ame) Lewis, was born on March 30, 1806 in the rural village of Freehold in Monmouth County, New Jersey. He was the youngest of ten children. At age four, Egbert was brought to Western New York by his parents. Much of his childhood was spent in Williamson and Pultneyville. Only two of his siblings moved to Palmyra: his brother Philip Grandin, a partner in Thayer & Grandin Row, and his sister Anna Grandin, the wife of Frederick Smith—a trustee of the Western Presbyterian Church.

Resident of Palmyra

At age eighteen, Egbert worked as an apprentice to Pomeroy Tucker in the Wayne Sentinel office. Pomeroy Tucker had learned the print trade in the Thurlow Weed newspaper office in Rochester. The Wayne Sentinel was a weekly pro-masonic newspaper that began publishing in 1823. Egbert became an apprentice just one year from the date of the first issue of the Wayne Sentinel.

At age twenty-two, Egbert became the third editor of the Wayne Sentinel, following Pomeroy Tucker and John H. Gilbert. Egbert purchased the Wayne Sentinel and bookstore on April 13, 1827 from John H. Gilbert. Gilbert stayed on as an employee. The Geneva Gazette of April 25, 1827 acknowledged the purchase: “Egbert B. Grandin has purchased the Palmyra Sentinel establishment, and we wish him abundant success in continuing the publication of the paper.”

The Year 1828

On June 14, 1828, Martin Harris carried the 116 pages to Palmyra. He had the manuscript in his possession until about July 7, 1828. Martin showed the manuscript to any “prudent” person who called. Would Egbert B. Grandin be considered a prudent person in 1828? Egbert was twenty-two years old. Putting it in perspective, Joseph Smith Jr. was twenty-three years old. Egbert had recently become the editor and proprietor of the Wayne Sentinel, the largest circulated newspaper in Palmyra. As his own editor and reporter, he would be privy to the fact that Martin Harris had a manuscript of interest. Since he lived in Martin’s neighborhood, Egbert may have stopped by to see him. Within a year he wrote, “Harris was his friend.”[1]

Thayer & Grandin Row

In the fall of 1828, Philip Grandin, Levi Thayer, and Joel Thayer (the brother-in-law of John H. Gilbert) completed construction of their row of commercial stores on Main Street in Palmyra. In October 1828, Egbert moved his newspaper business into the Thayer & Grandin Row (today 219 Main Street) and advertised that the Wayne Sentinel could be had for $2.15 per annum for village subscribers.[2]

By November 1828, Egbert had moved his book binding operation and circulating library into the rear room on the second floor of Thayer & Grandin Row. His business occupied the first and third floors of the west bay. Thomas Baldwin also had office space in the front portion of the second story of Thayer & Grandin Row. To get to his office, Thomas had to climb up the Main Street central stairway or go through Grandin’s office. Other merchants in the Thayer & Grandin Row included a tailor, a sash maker, and a dry-goods businessman.[3]

Marriage

Adding to his growing social stature in Palmyra, Egbert B. Grandin married Harriet Rogers, niece of Thomas Rogers II, on December 23, 1828 in Palmyra. In so doing, Egbert became the brother-in-law of Pomeroy Tucker, the newspaper man he had worked for four years earlier.

Publisher of the Book of Mormon

In 1829, Joseph Smith Jr. gave Egbert B. Grandin a few sheets of the Book of Mormon manuscript and a copy of the title page. His purpose in so doing was for Egbert to calculate the cost of publishing the Book of Mormon. Egbert wrote, “It is pretended that the title page will be published as soon as the translation is completed.” According to one antagonistic source, Egbert “at once expressed his disinclination to entertain the proposal to print at any price, believing the whole affair to be a wicked imposture and a scheme to defraud Mr. Harris, who was his friend, and who he advised accordingly.”[4]

Before signing with a publisher in Rochester, Joseph Smith Jr. went back to Egbert B. Grandin and asked him to reconsider publishing the Book of Mormon. With “a little convincing from his associates,” Egbert “decided that he wanted to make a profit and that he would not be responsible for the book’s contents just by being the printer.”[5] Who were his associates? The obvious answer would be the former printers and owners of the Wayne Sentinel—Pomeroy Tucker and John H. Gilbert.

Egbert agreed to publish the Book of Mormon in June 1829 as a “business matter” with the understanding “among his friends and associates” that he was in no way related to the religion that the book represented. His use of the word “friends” widens the circle of who possibly voiced an opinion on Egbert’s decision to publish the Book of Mormon. According to his diary, Egbert had friends in all the churches in Palmyra—Quakers, Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians. Philip Grandin, his brother and landlord, did not encourage Egbert to publish the Book of Mormon. On December 4, 1833, Philip Grandin signed the “Testimony of 51 Neighbors,” later printed in Mormonism Unvailed.[6]

On August 15, 1829, Martin Harris entered a mortgage agreement with Egbert Grandin, promising that before the expiration of eighteen months from August 15, 1829, Martin would pay the requisite $3,000 to cover the publication costs for 5,000 copies of the Book of Mormon. In case of nonpayment of monies, the sale of Martin’s acreage (about 150 acres) would cover the cost of printing.

In 1829, with financial arrangements in place, Egbert B. Grandin hired men to help with the printing of the Book of Mormon. There is one telling statement from employee J. N. T. Tucker in a letter written on May 23, 1842 which suggests knowledge of the stolen 116 pages—“We laid one sheet in type, we laid it aside, and told Martin Harris it was lost, and there would be serious defection in the book in consequence, unless another sheet like the original could be produced. The announcement threw the old gentleman in quite an excitement.”[7]

The employees hired to work on the Book of Mormon in the Thayer & Grandin Row were—

Jacob H. Bortles: He was the journeyman of the Book of Mormon. By 1830, Jacob was part-owner of the Wayne Sentinel and owner of the lottery office in the bookstore. He advertised “Six prizes of 5000 dollars—one of 4,750—51,000—60 number Lottery—8 drawn ballots—Tickets and shares will be received and for sale.”[8]

Albert Chandler: He assisted with binding copies of the Book of Mormon.

Abner Cole: He used presses of the Wayne Sentinel to print the Palmyra Reflector. He was a compositor of the Book of Mormon.

John H. Gilbert: He was the chief compositor and typesetter of the Book of Mormon.

Daniel Hendrix: He set type and read proof pages of the Book of Mormon.

Luther Howard: He was a binder of the Book of Mormon.

Thomas McAuley: He was a journeyman for the Book of Mormon. He carried pages of the Book of Mormon to Henry O’Reilly in Rochester.

Robinson (boy): The son of Gain Robinson. He assisted in the printing of the Book of Mormon.

A. S. Sanford: He assisted with the printing of the Book of Mormon.

J. N. T. Tucker: He was a practical printer.

Pomeroy Tucker: He was a foreman and editor of the Wayne Sentinel and Book of Mormon.

Oramus Turner: He was an apprentice printer.

William Van Camp: He was a compositor of the Book of Mormon and worked on the Wayne Sentinel.

Financial Problems in conjunction with the Book of Mormon

There were four large financial problems for Egbert B. Grandin that stemmed from printing the Book of Mormon. The first involved Luther Howard, Egbert’s partner in binding the Book of Mormon. Luther dissolved his partnership with Egbert and moved his bindery to the third story of Beckwith and Anderson’s Brick Block. He took out bankruptcy in the summer of 1831. In July 1831, Egbert purchased binding equipment and stacks of Book of Mormon signatures from Luther. Luther then sued Egbert for money owed him for binding the Book of Mormon.

The second financial problem involved the agreement with Martin Harris to print the Book of Mormon. Behind the scenes on October 21, 1830, Thomas Rogers II became the assignee for the mortgage by paying the holder, Egbert B. Grandin, $2,000 in hand when Egbert had some pressing financial needs. Thomas received $3,000, the entire amount of the mortgage which he later obtained when Martin Harris sold the required acreage to cover the cost of printing the Book of Mormon. Martin sold 150 ¼ acres (later assessed as 151 ¼ acres) to Thomas Lakey, who was to pay Martin the specified $3,000 in a series of installments extending to October 1832. With those monies, Martin could then settle the long-standing debt of the printing costs.[9] The recipient of the $3,000 was not Egbert B. Grandin but Thomas Rogers II, the mortgage assignee since October 21, 1830.

The third financial problem was a lawsuit between Egbert B. Grandin and Nathaniel H. Beckwith. On December 4, 1830, Egbert wrote, “Attended a suit between Beckwith N. H. and myself. B. Plaintiff was served me on a note signed by L. Howard for about $2.98. I had set off of binding Book of Mormon, a note I bought of Ed. L. Townsend and one I bought of Tucker and Lathrop—both amounting to about eighty-five dollars. Binding worth seventy dollars.”[10] On December 15, the following was recorded, “Attended to business commenced yesterday . . . brought in a judgment for Nathaniel Beckwith of $180.”[11]

The fourth financial problem was the publication of Abner Cole’s Palmyra Reflector on presses of the Wayne Sentinel. On February 16, 1831, Egbert wrote of being threatened financially and physically by the Presbyterians of Palmyra:

Some threats have been made within a few days by some Presbyterians, that they would withdraw their patronage from my establishment in consequence of my printing the Reflector. Paid no attention to them. Complaints have also been made of my allowing discussions on religious subjects to be held in the bookstore—and that young converts were also attacked by someone when they entered the bookstore and suggestions have been made that such things might injure me. Truly these are singular times—complaints all came from Presbyterians.[12]

In 1833, Egbert sold his print business to the firm of Wilcox & Bortles. [13] It eventually fell into the hands of T. R. Strong, Pomeroy Tucker, and George Cuyler.[14]

There are many reasons why Egbert wanted out of publishing. The most interesting was surely the court case “The People vs. Egbert B. Grandin.” Egbert was indicted for libel against Israel J. Richardson, a political candidate for Congress in the 27th Congressional District. Egbert published in the Wayne Sentinel that he was in possession of an affidavit made and sworn to before Judge Frederick Smith, “depositing that a woman of color was seen to come out from Israel J. Richardson’s bedroom.” Grandin was acquitted of all libelous charges, but issues concerning his “tell all” attitude were not well-received by the “men of high standing” in Palmyra.[15]

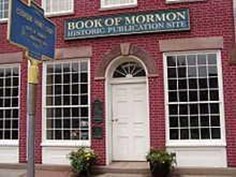

As for the Thayer & Grandin Row, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints purchased the structure. On March 26, 1998, the anniversary of the Book of Mormon first being available for purchase, the structure was dedicated by President Gordon B. Hinckley as the “Book of Mormon Historic Publication Site.”

Religious but without Affiliation

It would be interesting to know what Egbert B. Grandin thought of the Book of Mormon that he helped proofread with Oliver Cowdery. Unfortunately, Egbert’s only extant diary covers the years 1831 to 1841. His only mention of the Book of Mormon in the diary was on July 14, 1831 when he recorded spending “most of the day in moving Gold Bibles from Mr. Howard’s Bindery to my bookstore.” That was something he had to do because the man who had contracted to bind the book had gone bankrupt.[16] The term “Gold Bibles” suggests that he was not supportive of Joseph Smith or the Book of Mormon.

Egbert’s short diary entries show a definite interest in religion, but not a strong affiliation with one religion over another. For example, his diary reveals that Egbert attended Presbyterian, Baptist, Episcopal, Shaker, and Methodist meetings. Of these religious groups, he tells of his annoyance with the “Presbyterians” who complained that he “allowed discussions on religious subjects to be held in the bookstore.”[17] He does not write of annoyances with other religious groups. On March 21, 1830, he penned, “In evening, attended meeting at Methodist chapel. Four day meeting is being held. Mr. Hickey preached a very good discussion cutting Presbyterians.”[18]

In 1831, Egbert reported attending a Baptist Church.[19] From January 2 to January 12, 1831, he attended Presbyterian prayer meetings in the evenings.[20] On January 29, Egbert recorded, “Went towards evening to Daniel Durfee [a Quaker], who lives a few miles south of the village. He has a pretty looking wife – lives in a small log house. Mr. Durfee not at home.”[21] A few days later on February 2, he recorded, “Attended Baptist prayer meeting.”[22]

By 1834, Egbert’s interest in attending religious meetings had waned. His only entry about a church meeting in 1834 was on August 10:

Sunday—went to Baptist meeting in forenoon. At home in afternoon. Wife attended meeting all day . . . 15-20 negroes had assembled to take away a slave from—Williams who was on a visit from Washington—a good number of items were thrown against the house door and guns fired. The house was consequently injured. The sisters finally went off without the slaves—the others screamed—a distressing day.[23]

Even though his diary reveals that Egbert attended religious meetings, his attendance seemed to be more for social reasons than for worship.

Enterprising Young Man

Egbert B. Grandin turned his attention to civic matters. In 1831, Egbert was elected a Palmyra village trustee and the clerk of the Palmyra village board of election inspectors. He was appointed a collector of taxes in Palmyra and a member of the schoolboard. He was named constable in 1835 and town assessor in 1839. His civic positions placed him as an officer in the community, but not as a “man of high standing.” Egbert never achieved the same social status as Henry Jessup or George Beckwith.

Egbert recorded many interesting incidents in Palmyra, including on September 25, 1832, “In printing office in morning. In afternoon attended Chase auction. In evening also. I saw a knockdown between [Alexander] McIntyre and [Durfee] Chase.” None of his records suggest knowledge of the whereabouts of the 116 pages.[24]

Together with Henry Gardner, Egbert B. Grandin owned a butchery and tannery in town. Their partnership ended in April 1837. Gardner continued with the tannery, offering “Sole, Upper, Harness, Bridle, Collar, Top and Sip Leather and Calf, and Sheep Skins” for low cash.”[25] Whether under the management of Egbert or Henry Gardner, the business never was on the same level as the tannery and shoe business of Henry Jessup. Egbert also had a storage and freighting business, but again the “big money” in town beat him out. Egbert was not able to compete financially with the men of high standing, but he had some success as a farmer and politician. He was a spokesman for the Jacksonian party in Palmyra, organized to promote Andrew Jackson for US President. He was also a proponent of Masonry, although there is no record tying him to the masonic lodge in Palmyra.

Death of Egbert B. Grandin

On April 16, 1845, Egbert B. Grandin died of pneumonia in Palmyra at age thirty-nine. He was buried in Section R, Lot 111 in the Palmyra City Cemetery.

Three years after his death on August 23, 1848, his widow Harriet Rogers Grandin married Stephen Titcomb, a wealthy English businessman of Waterford Village on the Hudson River north of Albany, New York. In 1856, Harriet wrote to “Brigham Young or Joseph Smith Jun. I don’t know which I ought to address.” The letter read, “No doubt you have a distinct recollection of Mr. E. B. Grandin the man who printed your Bible.” Harriet outlined the course of her life, perhaps exaggerating her difficulties: “I am now living with a second husband who is now weary of my children and unwilling to have them with him any longer.” Regardless of Stephen Titcomb’s willingness, Harriet’s children continued to live with the couple until they were old enough to marry and move away. Harriet’s youngest daughter lived under Titcomb’s roof until she was thirty-seven years old.

Harriet then came to the real point of her letter:

The thought occurred to me that your people might take pleasure in contributing out of their abundance something which would help me to give my daughters advantages so as to enable them to maintain themselves. I would like to give them a little more education so as to fit them for teachers. The oldest one has a fine talent for music with a little more instruction she could maintain herself.[26]

Brigham Young did not respond.

Harriet tried again in 1874, the year before her death, reminding Brigham Young of her identity as the wife of E. B. Grandin, “the man who printed your Golden Bible,” and asked once more for a donation. She wrote of her husband, Stephen Titcomb, being ill: “His cure is hopeless, being softening of the brain.” She closed, “How I would like to visit your people.”[27] On April 22, 1875, Harriet Grandin Titcomb died in Waterford, New York. Her remains were brought to Palmyra so she could be buried next to her husband Egbert B. Grandin.

Children of Egbert Bratt and Harriet Rogers Grandin

1. Carlton Rogers Grandin (November 23, 1829–November 14, 1837). He died of typhus fever and the swelling of his leg.

2. Mary Sophia Grandin (June 21, 1831–February 18, 1886). She was married to Edwin H. Cheever (1819–1883) on April 18, 1855 in New York.

3. Edwin Grandin (1833).

4. Ellen Amanda Grandin (April 18, 1833–December 26, 1877). She was married to William Andrus on January 27, 1858. She resided in Waterford, New York from 1850 to 1855.

5. William Edward Grandin (December 8, 1834–November 1858). He was a druggist. He resided in Waterford, New York from 1850 to 1855. He did not marry.

6. Harriet Aurelia Grandin (December 25, 1837–May 8, 1933). She resided in Waterford, New York from 1850 to 1855. She married Frederick Allen (1836–1924) on October 7, 1874 in Waterford. She resided in Auburn, New York from 1880 to 1920.

7. Carlton Pomeroy Grandin (July 17, 1840–July 15, 1888). He was residing in Williamson, New York in 1850. He married Mary Jane Hinman (1841–1932) on November 11, 1867 in Battle Creek, Michigan. In 1880, he was residing in Battle Creek, Michigan.

[1] Tucker, Origin, Rise, and Progress of Mormonism, p. 51.

[2] “Published every Friday Morning, by E. B. Grandin,” Wayne Sentinel, October 19, 1827.

[3] Susan Easton Black and Harvey B. Black, “Exhibit Guide: Book of Mormon Historic Publication Site: Grandin Press,” pp. 18, 44.

[4] Tucker, Origin, Rise, and Progress of Mormonism, p. 51.

[5] Alexa Erekson, “1001 facts about the Prophet Joseph Smith.” In author’s possession.

[6] Howe, Mormonism Unvailed, pp. 366–367.

[7] J. N. T. Tucker newspaper article. In author’s possession.

[8] “New Lottery Office,” The Palmyra Reflector, July 27, 1830.

[9] Egbert B. Grandin to Thomas Rogers II, Wayne County Book of Mortgages, October 21, 1830, recorded May 23, 1832, 5:363.

[10] Egbert B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[11] Egbert B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[12] Egbert B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[13] “New Arrangement,” The Wayne Sentinel, May 15, 1833.

[14] “Death of George W. Cuyler,” Durfee Scrapbook, no. 3, 1876–1883.

[15] Newspaper clipping in the Palmyra Community Library; Seneca Farmer [Waterloo, NY], April 15, 1829.

[16] Smith, History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, pp. 115, 149; Weight, Miracle on Palmyra’s Main Street, pp. 13–15; Black and Black, “Exhibition Guide: Book of Mormon Historic Site,” pp. 104, 114, 120; Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 2: 406; “Grandin, Egbert Bratt,” in Joseph Smith Papers; “Printer’s Manuscript of the Book of Mormon, circa August 1829–circa January 1830,” inJoseph Smith Papers.

[17] E. B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[18] E. B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[19] E. B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[20] E. B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[21] E. B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[22] E. B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[23] E. B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[24] E. B. Grandin Diary, 1831–1841.

[25] “Dissolution,” Wayne Sentinel, April 17, 1837.

[26] Letter of Harriet Grandin Titcomb, 1856. Church History Library.

[27] Letter of Harriet Grandin Titcomb, 1856.